Goal Area 4: Identifying and Eliminating Tobacco-Related Disparities

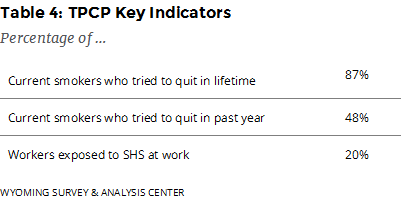

The fourth goal of the Wyoming TPCP and the CDC is to reduce tobacco use and associated health burdens among populations that are disparately affected by tobacco and related disease and death. For each of Wyoming’s high-priority subpopulations, we report on the key indicators of smoking prevalence compared to the rest of the adult population, quit attempts, and exposure to SHS at work. As reference points, the overall estimates for each of these indicators are presented in Table 4. Because of the relatively small number of smokers within each subpopulation, there is a high degree of uncertainty around the estimates for most of the subgroups. Often, this makes interpretation of statistical tests problematic. Therefore, we took a conservative approach and chose not to provide interpretations for statistical tests in which we had a low degree of confidence.

The fourth goal of the Wyoming TPCP and the CDC is to reduce tobacco use and associated health burdens among populations that are disparately affected by tobacco and related disease and death. For each of Wyoming’s high-priority subpopulations, we report on the key indicators of smoking prevalence compared to the rest of the adult population, quit attempts, and exposure to SHS at work. As reference points, the overall estimates for each of these indicators are presented in Table 4. Because of the relatively small number of smokers within each subpopulation, there is a high degree of uncertainty around the estimates for most of the subgroups. Often, this makes interpretation of statistical tests problematic. Therefore, we took a conservative approach and chose not to provide interpretations for statistical tests in which we had a low degree of confidence.

American Indian

To produce estimates for American Indians in Wyoming, WYSAC analyzed adults who considered themselves to be American Indian, including those who self-identified as multiracial including American Indian, regardless of whether they reported Hispanic ethnicity.

To produce estimates for American Indians in Wyoming, WYSAC analyzed adults who considered themselves to be American Indian, including those who self-identified as multiracial including American Indian, regardless of whether they reported Hispanic ethnicity.

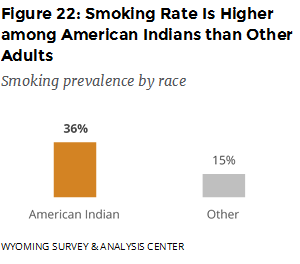

In 2017, 36% of American Indians smoked cigarettes, about double the smoking rate of the rest of the population 15% (Figure 22).

At some point in their lives, about nine out of every ten American Indian current smokers (89%) had stopped smoking for at least one day because they were trying to quit for good. About two thirds (63%) of American Indian current smokers had tried to quit smoking at least once in the past year.

Most employed American Indian adults were not regularly exposed to SHS at their workplace either indoors or outdoors. In 2017, 34% reported they had breathed someone else’s smoke at their workplace in the past seven days. American Indian workers were significantly more likely to be exposed to SHS than other workers.

Mental Health

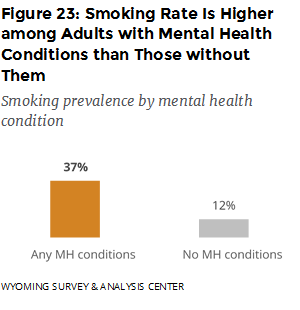

The 2017 ATS asked respondents “Do you have any mental health conditions, such as anxiety disorder, depression disorder, bipolar disorder, alcohol abuse, drug abuse, or schizophrenia?” About one fifth (18%) of adults reported having at least one mental health condition.

The 2017 ATS asked respondents “Do you have any mental health conditions, such as anxiety disorder, depression disorder, bipolar disorder, alcohol abuse, drug abuse, or schizophrenia?” About one fifth (18%) of adults reported having at least one mental health condition.

In 2017, 37% of adults with self-reported mental health conditions smoked cigarettes, more than double the smoking rate (12%) of those without self-reported mental health conditions (Figure 23).

At some point in their lives, about eight out of ten (82%) current smokers with mental health conditions had stopped smoking for at least one day because they were trying to quit for good. About half (48%) of current smokers with mental health conditions had tried to quit smoking at least once in the past year.

Most employed adults with mental health conditions were not regularly exposed to SHS at their workplace either indoors or outdoors. In 2017, 32% reported they had breathed someone else’s smoke at their workplace in the past seven days. Workers with mental health conditions were significantly more likely to be exposed to SHS than those with no mental health conditions.

Annual Household Income

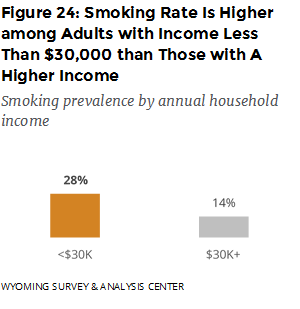

In 2017, 28% of adults with annual household income less than $30,000 smoked cigarettes, about double the smoking rate (14%) of those with a higher income (Figure 24).

At some point in their lives, about nine out of ten (89%) current smokers with income less than $30,000 had stopped smoking for at least one day because they were trying to quit for good; 44% had tried to quit smoking at least once in the past year.

Most employed adults with income less than $30,000 were not regularly exposed to SHS at their workplace either indoors or outdoors. In 2017, 26% reported that they had breathed someone else’s smoke at their workplace in the past seven days. For employed adults with income of $30,000 or more, 19% reported that they were exposed to SHS at their workplace. The difference by income was not statistically significant.

Young Adults

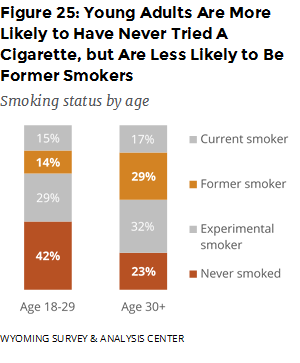

In 2017, 15% of young adults (ages 18 to 29) smoked cigarettes, comparable to the smoking rate (17%) of other adults (ages 30 or older; Figure 25). Young adults are more likely to have never tried a cigarette: 42% of young adults have never tried a cigarette as opposed to 23% of other adults. Because so few adults begin smoking after the age of 21, this difference between age cohorts may indicate that experimentation with tobacco products is becoming less common over time. Or, it may reflect experimentation that occurs at a later age and does not develop into regular smoking. Young adults are also less likely to be former smokers than other adults: 14% of young adults are formers smokers, compared to 29% of other adults. This disparity between age cohorts may reflect greater motivation to quit, such as in response to more noticeable health effects of smoking as people age.

In 2017, 15% of young adults (ages 18 to 29) smoked cigarettes, comparable to the smoking rate (17%) of other adults (ages 30 or older; Figure 25). Young adults are more likely to have never tried a cigarette: 42% of young adults have never tried a cigarette as opposed to 23% of other adults. Because so few adults begin smoking after the age of 21, this difference between age cohorts may indicate that experimentation with tobacco products is becoming less common over time. Or, it may reflect experimentation that occurs at a later age and does not develop into regular smoking. Young adults are also less likely to be former smokers than other adults: 14% of young adults are formers smokers, compared to 29% of other adults. This disparity between age cohorts may reflect greater motivation to quit, such as in response to more noticeable health effects of smoking as people age.

At some point in their lives, young adult current smokers (95%) were more likely than other current smokers (84%) to have stopped smoking for at least one day because they were trying to quit for good. Also, young adult smokers (67%) were more likely than other smokers (43%) to have tried to quit smoking at least once in the past year.

Significantly more young adults were exposed to SHS at their workplace (30%) than other working adults (17%).

Conclusions

American Indians, adults with mental health conditions, and those with annual household income less than $30,000 have relatively high smoking rates. Therefore, members of these populations are likely to suffer more from the health and economic burdens of tobacco use than are other adults. Many young adults (ages 18 to 29) have never tried a cigarette, but the smoking rate for young adults is comparable to the smoking rate for other adults (ages 30 or older). Preventing initiation and promoting cessation among young adults may reduce tobacco-related health risks later in their life.

Most current smokers have tried to quit cigarette smoking at some point in their lives. Young adult smokers are more likely to try to quit smoking than other adults. Focused efforts to help them succeed may reduce the risk of them developing smoking-related diseases later in life.

American Indians, adults with mental health conditions, and young adults have a higher risk of being exposed to SHS at their workplace either indoors or outdoors. While efforts to reduce secondhand smoke exposure in the workplace would benefit all Wyoming residents, these populations could see the most benefit from instituting such policies.