Goal Area 3: Promoting Cessation

The Wyoming TPCP and the CDC share the goal of reducing the health burdens of tobacco use by promoting quitting among adults and young people.

Smokers’ Cessation Efforts

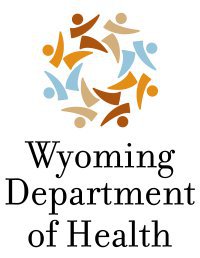

The majority (69%) of current smokers stated they wanted to quit, 26% said they did not, and 6% said they did not know or were not sure. At some point in their lives, most current smokers (87%) had stopped smoking for at least one day because they were trying to quit for good. About half of current smokers (48%) had tried to quit smoking at least once in the past year (Figure 16), which has not changed significantly since comparable questions were first asked in 2010.

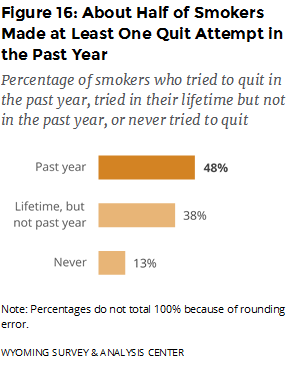

Relatively few smokers who had tried to quit in the past year had used proven cessation aids (Figure 17). When they did use proven cessation aids, nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) was the most often used, consistently since 2012, when comparable questions were first asked.

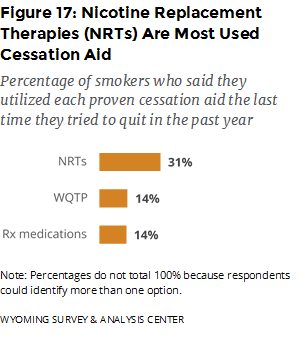

When they had tried to quit or wanted to quit, most smokers faced obstacles to quitting cigarette smoking. The most common barriers were loss of a way to handle stress and cravings for a cigarette, followed by other people smoking around them (Figure 18). Thus, smokefree indoor air policies and reducing exposure to secondhand smoke could help many smokers who are trying to quit.

ENDS Users’ Cessation Efforts

Although the adult population of current ENDS users is relatively small (6% of adults) and ENDS are a relatively new type of tobacco product, some of them still tried to quit using ENDS for good. At some point in their lives, about one quarter of current ENDS users (24%) had stopped using ENDS for at least one day because they were trying to quit for good. About one fifth of current ENDS users (19%) had tried to quit using ENDS at least once in the past year.

Involvement of Healthcare Providers in Tobacco Cessation

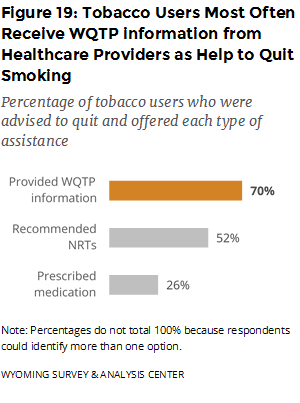

The ATS asked tobacco users if they had seen a healthcare professional in the past year and if so, if they received advice to quit from a healthcare professional. The majority (75%) of tobacco users had seen a healthcare professional in the past year. About half (55%) of these tobacco users were advised by a health professional to quit using tobacco. This result has remained stable since comparable questions were first asked in 2010. These respondents then answered more detailed questions about whether and how healthcare providers provided assistance. In 2017, 63% of tobacco users who were advised to quit were also offered assistance to quit from their healthcare providers. These tobacco users most often received information about the Wyoming Quit Tobacco Program (WQTP) from their healthcare providers (Figure 19).

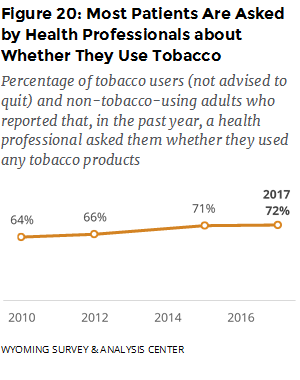

In a separate line of questioning, in the past year, 72% of tobacco users who were not advised to quit and non-tobacco-using adults reported that a health professional asked them whether they smoked cigarettes or used other forms of tobacco (Figure 20). This is a significant increase over time, going from 64% in 2010, when comparable questions were first asked, to 72% in 2017. Thus, healthcare professionals seem to be more frequently screening their patients for tobacco use. This increase coincides with changes related to the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, though we cannot make a causal attribution to the requirements of that law. Still, 13% of tobacco users were not advised to quit nor screened for tobacco use.

Tobacco Cessation and Tobacco Tax

Tobacco Cessation and Tobacco Tax

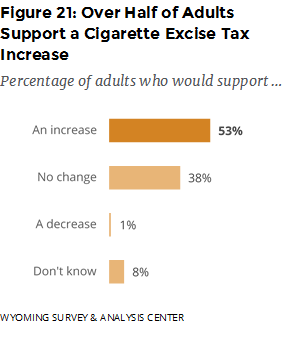

Increasing the price of tobacco products is one method of encouraging the cessation of tobacco use (CDC, 2015) and discouraging the initiation of tobacco use (CDC, 2014b). Since 2003, the state of Wyoming has taxed cigarettes with an excise tax of $0.60 per pack. When asked how much of an increase above $0.60 they would approve, over half (53%) of adults would approve an increase of some amount (Figure 21). The most popular amount was an increase of $1.50 or more, with 20% of adults supporting that change. For smokeless tobacco, over half (55%) of adults indicated that they were “for” an increase in the tax while 38% said they were “against,” and 7% said that they did not know or were not sure.

Appendix A includes data on price smokers paid for a pack or carton of cigarettes and use of special promotions to buy cigarettes.

Conclusions

The majority of smokers have tried to quit at some point in their lives and want to quit for good. However, the use of proven cessation aids is relatively low. When they had tried to quit or wanted to quit, most smokers faced obstacles such as loss of a way to handle stress, cravings for a cigarette, and other people smoking around them. Although it may be difficult for tobacco prevention efforts to help with the first two obstacles, reducing exposure to secondhand smoke could help many smokers who are trying to quit.

The majority of smokers have tried to quit at some point in their lives and want to quit for good. However, the use of proven cessation aids is relatively low. When they had tried to quit or wanted to quit, most smokers faced obstacles such as loss of a way to handle stress, cravings for a cigarette, and other people smoking around them. Although it may be difficult for tobacco prevention efforts to help with the first two obstacles, reducing exposure to secondhand smoke could help many smokers who are trying to quit.

Many tobacco users are not receiving screening and assistance from healthcare providers to help them quit. About half of tobacco users who saw a healthcare professional in the previous year were advised to quit, and about one third of those were not offered assistance. Greater collaboration with health professionals could result in more tobacco users becoming aware of, and receptive to, cessation services (CDC, 2015).

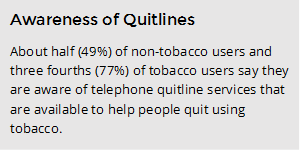

Awareness of tobacco quitlines is another area for potential improvement. About half of non-tobacco users were aware that a quitline existed. Friends and family of tobacco users (which would include non-tobacco users) are key referral sources for many WQTP enrollees (WYSAC, 2017). If more non-tobacco users knew about the existence of this proven cessation aid, then they could inform and encourage tobacco users who may not know about it.