Goal Area 3: Promoting Cessation

Goal Area 3: Promoting Cessation

The TPCP and the CDC share the goal of reducing the health burdens of tobacco use by promoting quitting among adults and young people.

Smokers’ Cessation Efforts

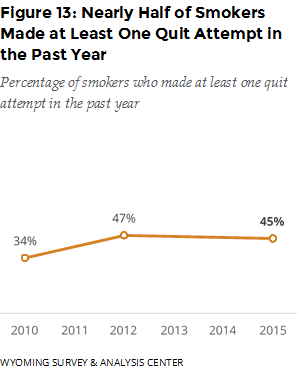

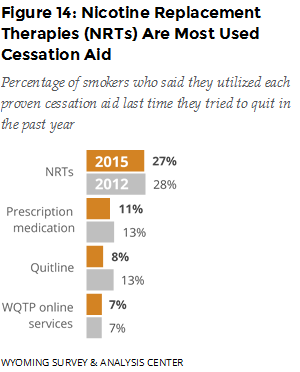

The majority (68%) of current smokers stated that they wanted to quit, 26% said they did not, and 6% responded that they did not know or were not sure. At some point in their lives, most current smokers (86%) had stopped smoking for at least one day because they were trying to quit for good. Nearly half of current smokers (45%) had tried to quit smoking at least once in the past year (Figure 13). This has not changed significantly since 2010. Relatively few smokers who had tried to quit in the past year had used proven cessation aids. When they did use them, nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) was the most often used in both 2012 and 2015 (Figure 14).

Involvement of Healthcare Providers in Tobacco Cessation

The ATS asked tobacco users if they had seen a healthcare professional in the past year and if so, if they received advice to quit from a healthcare professional. Half (50%) of these current tobacco users were advised by a health professional to quit using tobacco. This result has remained stable since 2010. These respondents then answered more detailed questions about whether and how healthcare providers provided assistance. In 2015, 63% of tobacco users who were advised to quit were also offered assistance to quit from their healthcare providers. These tobacco users most often received information about the Wyoming Quit Tobacco Program (WQTP) from their healthcare providers (Figure 15).

The ATS asked tobacco users if they had seen a healthcare professional in the past year and if so, if they received advice to quit from a healthcare professional. Half (50%) of these current tobacco users were advised by a health professional to quit using tobacco. This result has remained stable since 2010. These respondents then answered more detailed questions about whether and how healthcare providers provided assistance. In 2015, 63% of tobacco users who were advised to quit were also offered assistance to quit from their healthcare providers. These tobacco users most often received information about the Wyoming Quit Tobacco Program (WQTP) from their healthcare providers (Figure 15).

In a separate line of questioning, the majority (71%) of current tobacco users who had not been advised to quit and non-tobacco-using Wyoming adults reported that a healthcare professional had asked them whether they smoked cigarettes or used other forms of tobacco. This is a significant increase over time, going from 64% in 2010 to 66% in 2012 to 71% in 2015.

Tobacco Cessation and the Price of Tobacco

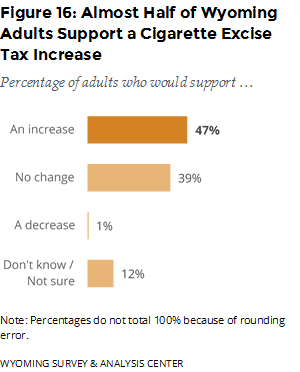

Increasing the price of tobacco products is one method of encouraging cessation (CDC, 2015). Since 2003, the state of Wyoming has taxed cigarettes with an excise tax of $0.60 per pack. When asked how much of an increase above $0.60 they would approve, almost half (47%) of adults would approve an increase of some amount (Figure 16). The most popular amount was an increase of $1.50 or more, with 21% of adults supporting that change. For smokeless tobacco, 49% of adults indicated that they were “for” an increase in the tax while 40% said they were “against,” and 10% said that they did not know or were not sure.

Increasing the price of tobacco products is one method of encouraging cessation (CDC, 2015). Since 2003, the state of Wyoming has taxed cigarettes with an excise tax of $0.60 per pack. When asked how much of an increase above $0.60 they would approve, almost half (47%) of adults would approve an increase of some amount (Figure 16). The most popular amount was an increase of $1.50 or more, with 21% of adults supporting that change. For smokeless tobacco, 49% of adults indicated that they were “for” an increase in the tax while 40% said they were “against,” and 10% said that they did not know or were not sure.

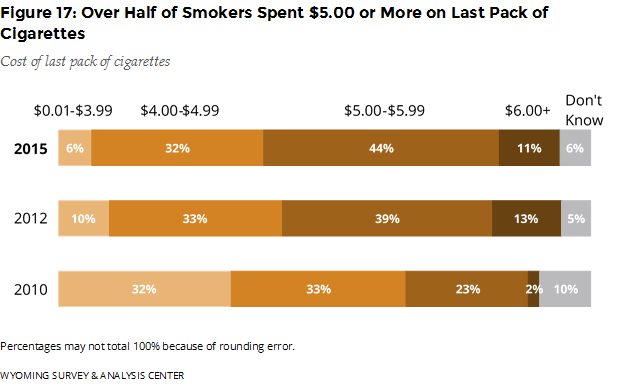

Most smokers (55%) were paying more than $5 per pack of cigarettes in 2015, a greater proportion than 2010 when it was just 25% (Figure 17).

In 2015, 79% of all Wyoming adults who had smoked and had bought cigarettes for themselves in the past 30 days, did not take advantage of coupons, rebates, buy 1 get 1 free, 2 for 1, or any other special promotion.

Conclusions

The majority of smokers have tried to quit and want to quit for good. They are also paying more for cigarettes than they have in the past. However, the use of proven cessation aids is relatively low. Many tobacco users are not receiving screening and assistance from healthcare providers to help them quit. Only half of current tobacco users who saw a healthcare professional in the previous year were advised to quit, but over half of those were offered assistance. Greater collaboration with health professionals could result in more tobacco users becoming aware of, and receptive to, cessation services.

Awareness of tobacco quitlines is another area of potential improvement. Less than half of nonsmokers were aware that a quitline (local or national) existed. The WQTP reports that friends and family of tobacco users (which would include non-tobacco users) are key referral sources (WYSAC, 2017). If more nonsmokers knew about the existence of this proven cessation aid, then they could inform and encourage tobacco users who may not know about it.

Goal Area 4: Identifying and Eliminating Tobacco-Related Disparities

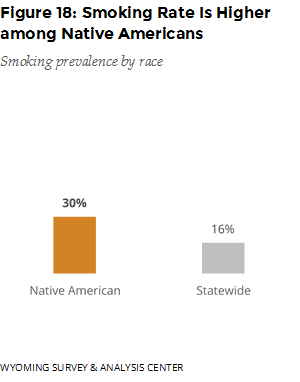

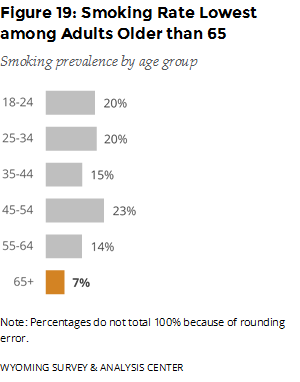

The fourth goal of the TPCP and the CDC is to reduce tobacco use and associated health burdens among populations that are disparately affected (Starr et al., 2005). In 2015, 30% of Native Americans in Wyoming smoked cigarettes, almost double the statewide smoking rate of 16% (Figure 18). Women and men in Wyoming smoked at about the same rate (15% vs 17% respectively); 18% of women of childbearing age (18–44 years old) were current smokers. Young adults (aged 18–24) were one of three age groups with a relatively high smoking rate (Figure 19).

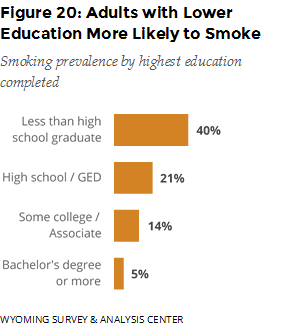

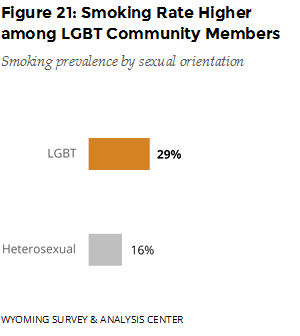

Those with less education were more likely to smoke (Figure 20). Adults who identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or “other” were more likely to smoke than those who identified as heterosexual (Figure 21).

Conclusions

Compared to the state rate, Native Americans, young adults, adults with less education, and those who identify as LGBT have relatively high smoking rates. Although the smoking rate among women of child-bearing age is not exceptionally high, the health burdens of smoking while pregnant are substantial. Promoting quitting and reducing initiation among these groups will, over time, reduce the disparities in tobacco use and its health consequences.