Goal Area 4: Identifying and Eliminating Smoking-Related Disparities

Generations-long inequities in social, economic, and environmental conditions contribute to poor health outcomes. Breakdowns by race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status may reflect where a person lives, works, or plays rather than the individual’s characteristics or personal choices (CDC, 2022c). These inequities have a greater impact on health outcomes than individual choices.

Addressing these health inequities is the fourth goal of the SUTPP and the CDC with the aim to reduce commercial tobacco and nicotine use and the related health burdens among populations disproportionately impacted by tobacco-related disease and death.

Starting in 2019, the SUTPP identified four priority groups in Wyoming that were unequally impacted by smoking: people with low incomes, people who identify as American Indian, people experiencing behavioral health conditions, and young adults (aged 18-29).

For each population and each smoking-related disparity, we analyzed three key indicators: the prevalence, quit attempts, and exposure to secondhand smoke.

Because of the small number of ATS respondents who were smokers within each priority population, there is a high degree of uncertainty around the estimates for most of these groups. Therefore, WYSAC took a cautious approach and chose not to provide interpretations for statistical tests in which we had a low degree of confidence, including when fewer than 50 adults responded to a question. Because of this issue, we do not report quit attempts for people with low incomes, American Indians, or young adults. We also do not report a prevalence rate for American Indians.

For context, the overall smoking rate in Wyoming adults is 16%.

Adults with Low Annual Household Income

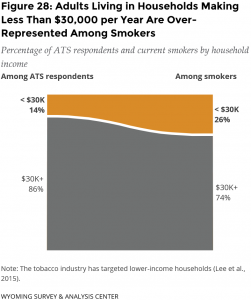

Tobacco industry marketing has targeted lower-income neighborhoods (Lee et al., 2015). With the tobacco industry’s pointed strategies toward people with lower incomes, adults with lower incomes have a disproportionately high rate of commercial tobacco and nicotine use.

An ideal measure for identifying people with low incomes would be the poverty level. However, this varies by size of household and other factors not included in the ATS. Based on practical considerations such as survey sample size, WYSAC and the SUTPP partners used a threshold of $30,000 in annual household income to identify adults with low incomes.

For context, the median household income for Wyoming adults is $65,304 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2021). By definition, half of the adults in the state have an annual income less than the median.

Smoking Prevalence

Adults with an annual household income of less than $30,000 (29%) had a significantly higher smoking rate than those with annual household incomes greater than $30,000 (14%).

Adults living in households making less than $30,000 per year are over-represented among smokers (Figure 28). Only 14% of adults who responded to the survey were living in households with an income of less than $30,000, yet they made up 26% of current smokers in the survey.

Exposure to Secondhand Smoke at Work

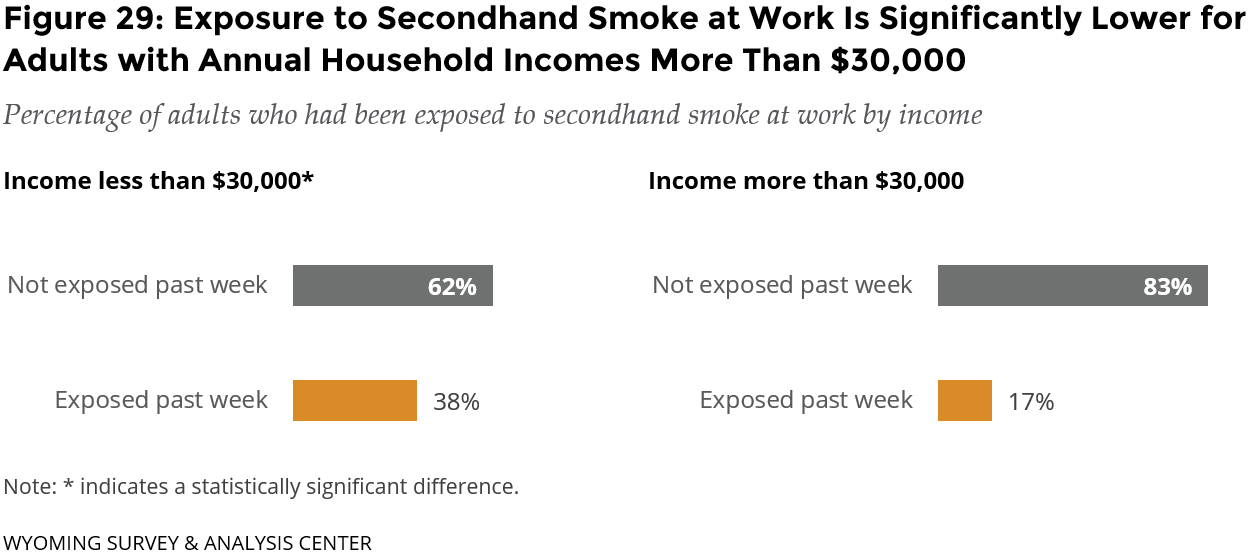

In 2021, 62% of adults with an annual income less than $30,000 were not exposed to someone else’s secondhand smoke at work. Significantly more adults with an annual income less than $30,000 were exposed to secondhand smoke at work than working adults with an annual income of $30,000 or more (Figure 29).

Occupational differences might explain this difference. For example, adults working in service industries are at a higher risk of exposure to secondhand smoke than those working in other industries (Holmes & Ling, 2017; Su et al., 2019), and they might have lower incomes. However, the ATS does not collect information about specific occupations.

American Indian

WYSAC acknowledges that different terms refer to the Indigenous populations of the U.S. when unable to refer to specific tribes. In this report, use of the term American Indian mirrors the CDC-suggested survey item used for the ATS.

Tobacco companies have long used the ceremonial significance of tobacco to encourage American Indians to use their commercial tobacco products (D’Silva et al., 2018). Tobacco companies have a history of targeting this community, beginning with using American Indian imagery and symbols in marketing, often depicting negative stereotypes. The tobacco industry misled these communities by providing financial support for their cultural events and providing highly discounted prices on commercial tobacco and nicotine products (Lempert & Glantz, 2019). The tobacco industry’s focused efforts have contributed to disproportionately high smoking rates for American Indians (D’Silva et al., 2018).

WYSAC considered respondents as American Indian when they self-identified as American Indian or multiracial including American Indian, regardless of whether they reported Hispanic ethnicity. This approach allowed for a larger sample from which to draw conclusions.

For context, American Indian and Alaska Native people make up 2.8% of the Wyoming population, although that number excludes American Indian and Alaska Natives who identify as more than one race or ethnicity including Hispanic or Latinx (U.S. Census Bureau, 2021).

Exposure to Secondhand Smoke at Work

In 2021, 80% of American Indian adults were not exposed to secondhand smoke at work. The difference between American Indian adults and non-American Indian adults who were exposed to secondhand smoke at work was not significantly different (Figure 30).

Behavioral Health

Historically, the tobacco industry has targeted people experiencing behavioral health conditions (such as depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, substance use disorder, and psychotic disorder; Prochaska et al., 2017; Campbell et al., 2016).

For this reason, studies (such as the Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2020; Talati et al., 2016) have demonstrated an association between cigarette smoking and behavioral health conditions. People with behavioral health conditions are more likely to smoke, and smokers with these conditions tend to smoke more cigarettes than smokers without behavioral health conditions (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2020).

For context, the 2021 ATS asked respondents “Do you have any mental health conditions, such as an anxiety disorder, depression disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) or substance use disorder?” About one fifth (22%) of adults reported having at least one behavioral health condition.

As with any self-report data, it is possible that people under-reported health conditions on the ATS, especially those conditions that may have stigma attached such as behavioral health conditions.

Smoking Prevalence

Adults with behavioral health conditions (28%) had a significantly higher smoking rate than those without a behavioral health condition (13%).

Adults with behavioral health conditions are over-represented among smokers (Figure 31). Only 22% of adults who responded to the survey reported having behavioral health conditions, yet they made up 39% of current smokers in the survey.

Current Smokers’ Quit Attempts: Lifetime and Past Year

Due in part to the small sample size for people with behavioral health conditions, the difference between quit attempts (including lifetime and past year) for smokers with behavioral health conditions and those without behavioral health conditions was not statistically significant.

Lifetime quit attempts:

- 77% of current smokers with behavioral health conditions had stopped smoking for at least one day because they were trying to quit for good, and

- 85% of current smokers without behavioral health conditions had stopped smoking for at least one day because they were trying to quit for good.

Past year quit attempts:

- 27% of current smokers with behavioral health conditions had tried to quit smoking at least once in the past year, and

- 35% of current smokers without behavioral health conditions had tried to quit smoking at least once in the past year.

Smokers’ Obstacles to Quitting Smoking Cigarettes

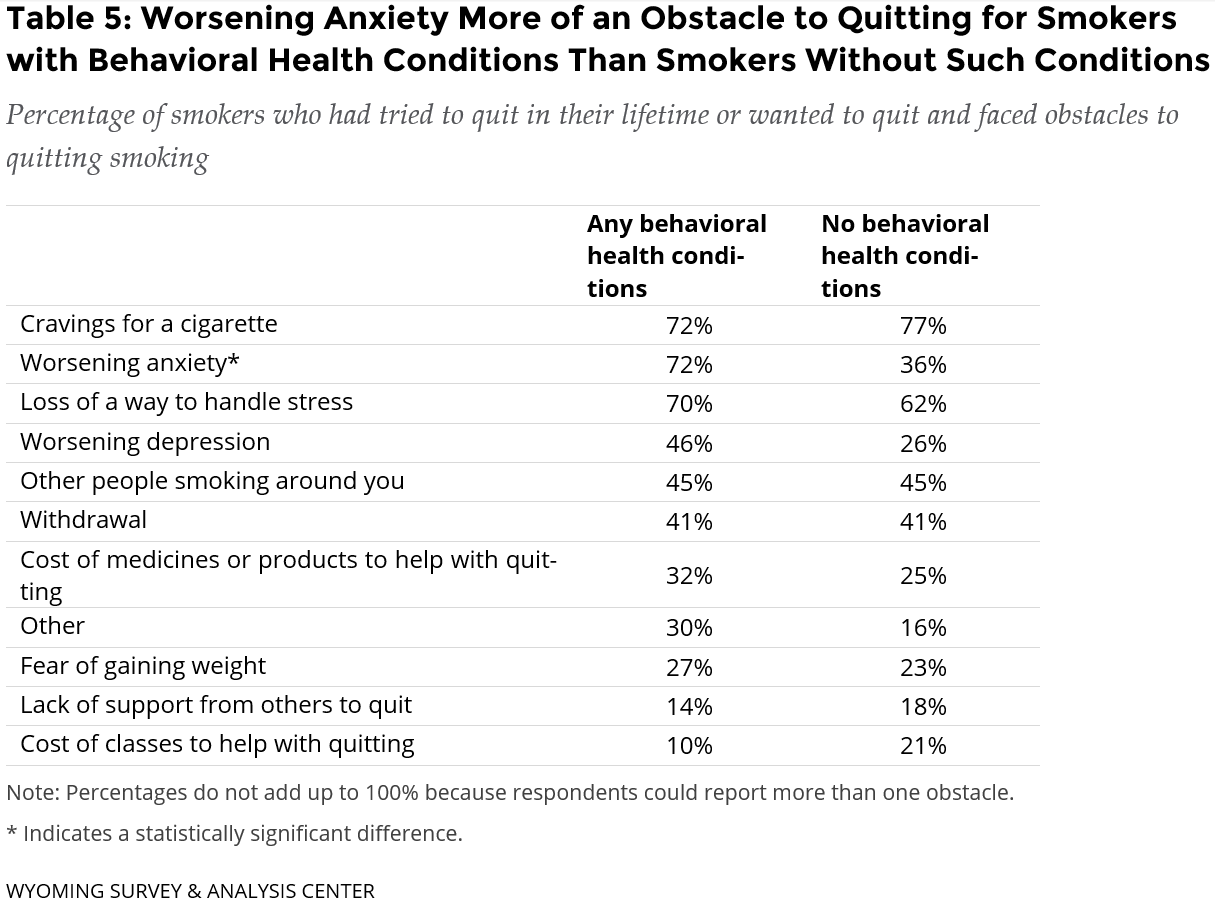

One obstacle to quitting was significantly more common among people with behavioral health conditions than among all others: worsening anxiety (Table 5).

Current smokers with behavioral health conditions noted the top three obstacles to quitting cigarettes as cravings for a cigarette (72%), worsening anxiety (72%), and the loss of a way to handle stress (70%). The Wyoming Quit Tobacco (WQT) program is designed to address the common barriers that adults face when quitting smoking, including these three obstacles.

Exposure to Secondhand Smoke at Work

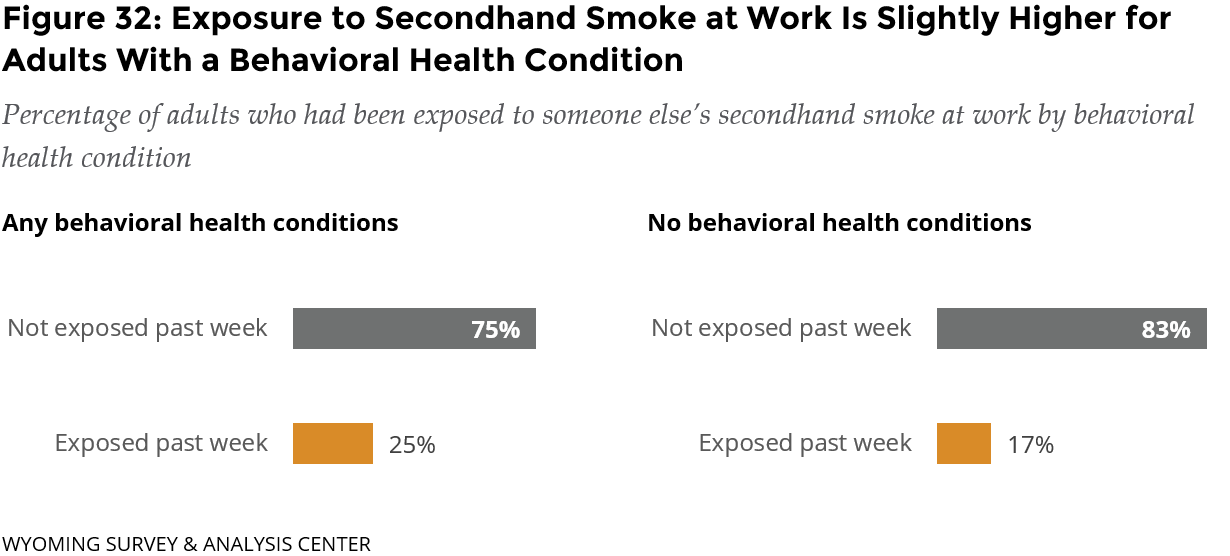

In 2021, 75% of adults with any behavioral health conditions were not exposed to someone else’s secondhand smoke at work. Slightly more adults with a behavioral health condition were exposed to secondhand smoke at work than adults without any behavioral health conditions (Figure 32). Due in part to the small sample size of people who reported behavioral health conditions, the difference between reports of secondhand smoke exposure was not statistically significant.

Young Adults

ATS data (see the Goal Area 1: Preventing Commercial Tobacco Use section) showed that most smokers start smoking as youths or young adults. Young adulthood is an impressionable stage when people may begin a lifelong smoking habit or a habit begun during adolescence could become set (Biener & Albers, 2004; Lee et al., 2020), making them a priority population. The tobacco industry has targeted young adults with advertising and marketing that promises to help them create the attractive, successful, and popular personas they seek (Farber & Folan, 2017). Industry campaigns promote messages, values, and product features designed specific to young adults (Lee et al., 2020). Tobacco companies place these campaigns in places young adults frequent most, such as colleges, fraternities, and bars (Ling & Glantz, 2002). With such targeted industry efforts, young adults are a priority population and require equally targeted efforts for commercial tobacco and nicotine prevention and control strategies.

WYSAC considered respondents as young adults when they were between the ages of 18 and 29 to increase the sample size and improve the reliability of estimates for this group. In 2021, Wyoming’s population of young adults was 87,642 (CDC, 2023).

Smoking Prevalence

The smoking rate of young adults (18%) was similar to the smoking rate of other adults (15%; Figure 33).

The smoking rate of young adults (18%) was similar to the smoking rate of other adults (15%; Figure 33).

However, young adults are about twice as likely to have never tried a cigarette: 41% of young adults have never tried a cigarette compared to 22% of other adults. Because so few adults begin smoking after the age of 21 (see the Goal Area 1: Preventing Commercial Tobacco Use section), this difference between age cohorts may indicate that experimentation with commercial tobacco and nicotine products is becoming less common over time. It may also demonstrate the collective success of CDC, SUTPP, multiple federal agencies, county prevention workers, and other groups.

Young adults were statistically significantly less likely to be former smokers (7%) compared to other adults (32%).

Young adults are more likely to use ENDS (18%), which may lead to later initiation of smoking cigarettes. More research is needed to investigate this potential pathway to smoking.

Table 6 details the four categories of smoking status used in Figure 33.

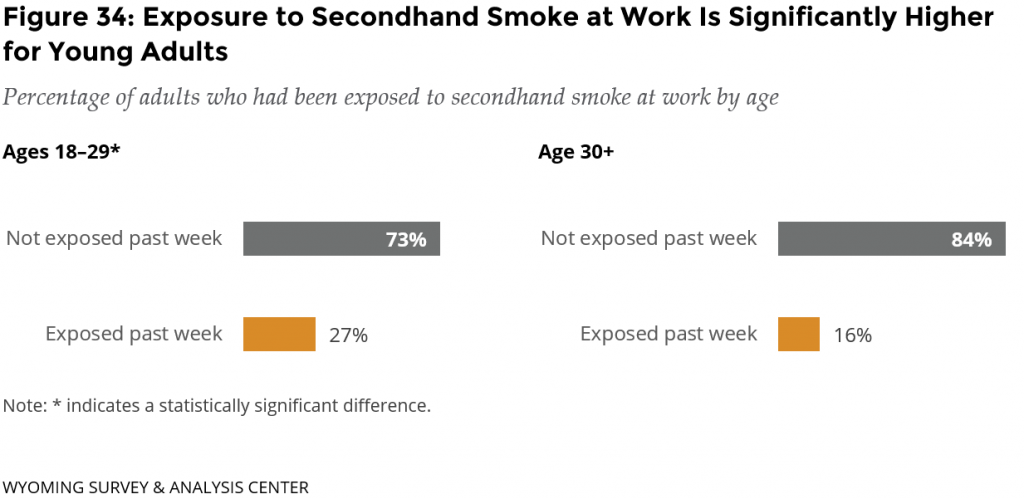

Exposure to Secondhand Smoke at Work

In 2021, 73% of young adults were not exposed to someone else’s secondhand smoke at work. Significantly more young adults were exposed to secondhand smoke at work than other working adults (Figure 34).

A possible explanation for this is an occupational disparity, as young adults who work in the service, maintenance, and transportation industries are at a higher risk of exposure to secondhand smoke than those working in other industries (Holmes & Ling, 2017). However, the ATS does not collect information about specific occupations.

Conclusions

The 2021 ATS data highlight the impact of the tobacco industry’s targeted efforts to engage already vulnerable populations in commercial tobacco use. People with low incomes, people who identify as American Indian, and people experiencing behavioral health conditions are disproportionately affected by smoking. Young adults (aged 18-29) are a priority population because young adulthood is an impressionable stage when people may begin a lifelong smoking habit (Biener & Albers, 2004; Lee et al., 2020).

Adults with an annual household income of less than $30,000 had a significantly higher smoking rate than those with annual household incomes greater than $30,000. They were also significantly more likely to be exposed to secondhand smoke at work.

Previous ATS results have shown a smoking disparity for American Indian adults. In 2021, too few smokers identified as American Indian to detect a smoking disparity.

People with behavioral health conditions were significantly more likely to smoke than those without a behavioral health condition. Current smokers with behavioral health conditions are significantly more likely to identify worsening anxiety as an obstacle to quitting than smokers without such conditions. Additional barriers for this group are craving cigarettes and the loss of a way to handle stress. Free coaching and free cessation aids from the WQT program address these obstacles.

Young adults were more likely to have never tried a cigarette compared to other adults.

These communities carry disproportionate burdens of smoking. Work related to Goal 4 of the SUTPP is essential to combat targeted efforts from the tobacco industry to eliminate these disparities and work toward health equity. Evidence-based ways to reduce these disparities include developing equitable policies, programs, and systems (CDC, 2022c).

Acknowledgement

Proportion plots adapted from a template distributed by Stephanie Evergreen: https://stephanieevergreen.com/proportion-plots/