Goal Area 4: Identifying and Eliminating Tobacco-Related Disparities

Generations-long inequities in social, economic, and environmental conditions contribute to adverse health outcomes. Breakdowns by race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status may reflect where a person lives, works, or plays rather than the individual’s characteristics or personal choices. These inequities have a greater impact on health outcomes than individual choices. For example, research shows the tobacco industry has targeted promotional efforts toward certain sociodemographic neighborhoods (D’Silva et al., 2018; Farber & Folan, 2017; Lee et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2013).

Addressing these health inequities is the fourth goal of the TPCP and the CDC with the aim to reduce tobacco use and the related health burdens among populations disproportionately impacted by tobacco-related disease and death.

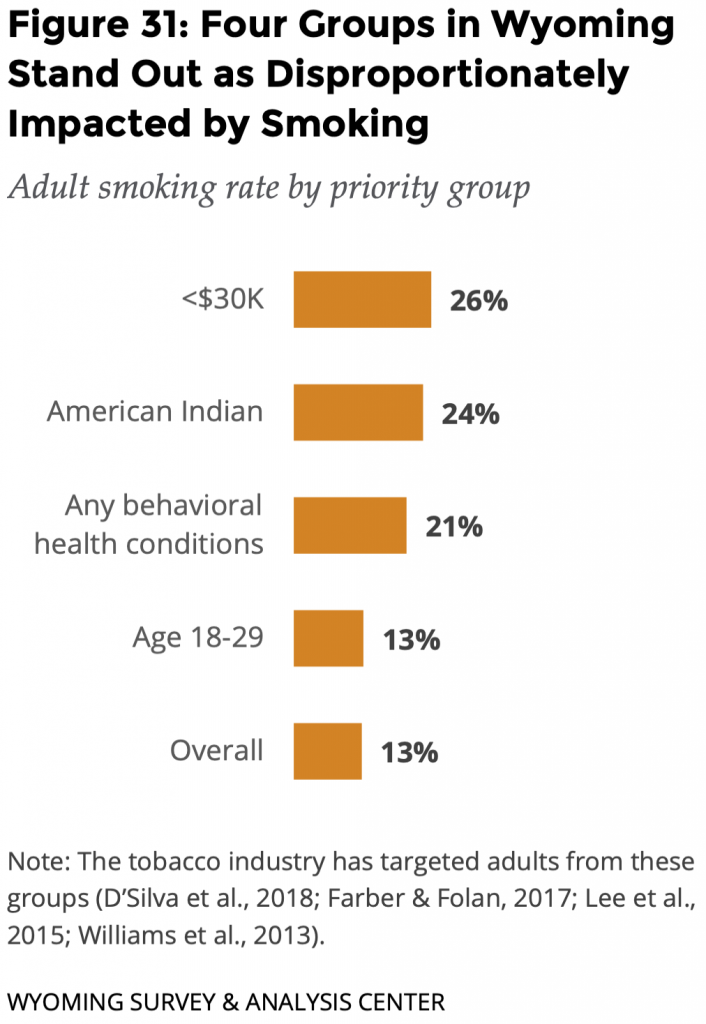

The TPCP focuses on people with low incomes, American Indians, people experiencing behavioral health conditions, and young adults (age 18-29) as priority populations (Figure 31). The tobacco industry has targeted each of these populations (D’Silva et al., 2018; Farber & Folan, 2017; Lee et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2013).

The TPCP focuses on people with low incomes, American Indians, people experiencing behavioral health conditions, and young adults (age 18-29) as priority populations (Figure 31). The tobacco industry has targeted each of these populations (D’Silva et al., 2018; Farber & Folan, 2017; Lee et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2013).

For each population, we analyzed three key indicators: the prevalence of smoking compared to the rest of the adult population, quit attempts, and exposure to secondhand smoke (SHS) at work.

Because of the relatively small number of ATS respondents who are smokers within each priority population, there is a high degree of uncertainty around the estimates for most of these groups. This makes interpretation of statistical tests problematic. Therefore, we took a cautious approach and chose not to provide interpretations for statistical tests in which we had a low degree of confidence, including when fewer than 50 adults responded to a question regardless of their answers to that question. This follows the example set by the CDC in reporting Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) statistics (https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/brfssprevalence/).

These low numbers and cautious approach make it difficult to explore the possible overlap of different factors that may be affecting these groups and contributing to inequalities. For example, when looking at people with self-reported behavioral health conditions and people in lower income households, there may be some overlap of these two groups. Because there are so few respondents in each category, we do not explore these intersections, limiting the conclusions.

Adults with Low Annual Household Income

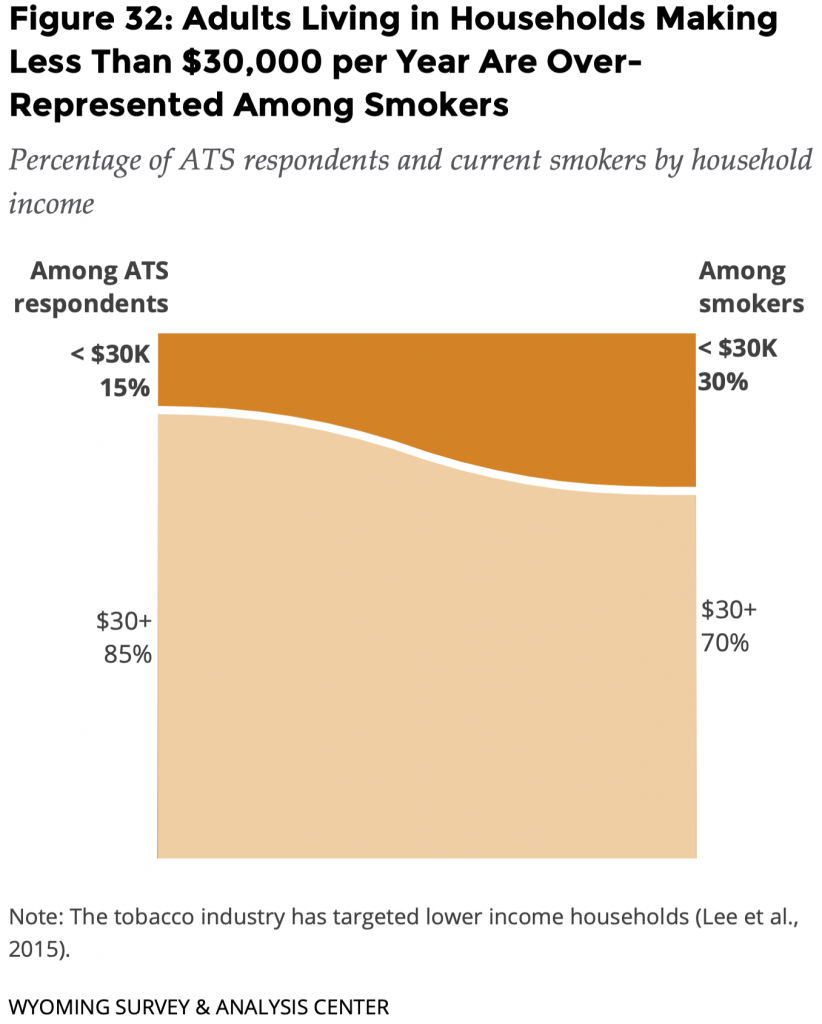

Tobacco industry marketing has traditionally targeted lower-income neighborhoods (Lee et al., 2015). Tobacco retailers are also more common in lower income neighborhoods (Young-Wolff et al., 2014). With the tobacco industry’s pointed strategies toward people with lower incomes, adults with lower incomes have a disproportionately high rate of tobacco use.

An ideal measure for identifying people with low incomes would be the poverty level. However, this varies by size of household and other factors not included in the ATS. Based on practical considerations such as survey sample size, WYSAC and the TPCP partners use a threshold of $30,000 in annual household income to identify adults with low incomes.

For context, the median household income for Wyoming adults is $64,049 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019). By definition, median means that half of the adults in the state have an annual income less than the median.

Smoking

About twice the percentage of adults with annual household incomes less than $30,000 smoked cigarettes (26%).

About twice the percentage of adults with annual household incomes less than $30,000 smoked cigarettes (26%).

Adults living in households making less than $30,000 per year are over-represented among smokers (Figure 32). Only 15% of adults who responded to the survey were living in households with an income of less than $30,000, yet they made up 30% of current smokers in the survey.

Current Smokers’ Quit Attempts: Lifetime and Past Year

Fewer than 50 current smokers said they live in households making less than $30,000 annually. That is insufficient data for a precise estimate of lifetime and past year quit attempts in this report. WYSAC is available to discuss the data and associated limitations with interested parties.

Exposure to SHS at Work

Due in part to the small sample size of adults with low incomes, the difference between reports of SHS exposure based on income was not statistically significant.

- 19% of adults with an annual income less than $30,000 reported that they were exposed to SHS at their workplace.

- 22% of adults with an annual income of $30,000 or more reported that they were exposed to SHS at their workplace.

American Indians

WYSAC acknowledges that different terms refer to the Indigenous population of the U.S. when unable to refer to specific tribes. In this report, use of the term American Indian mirrors the CDC-suggested survey item used for the ATS.

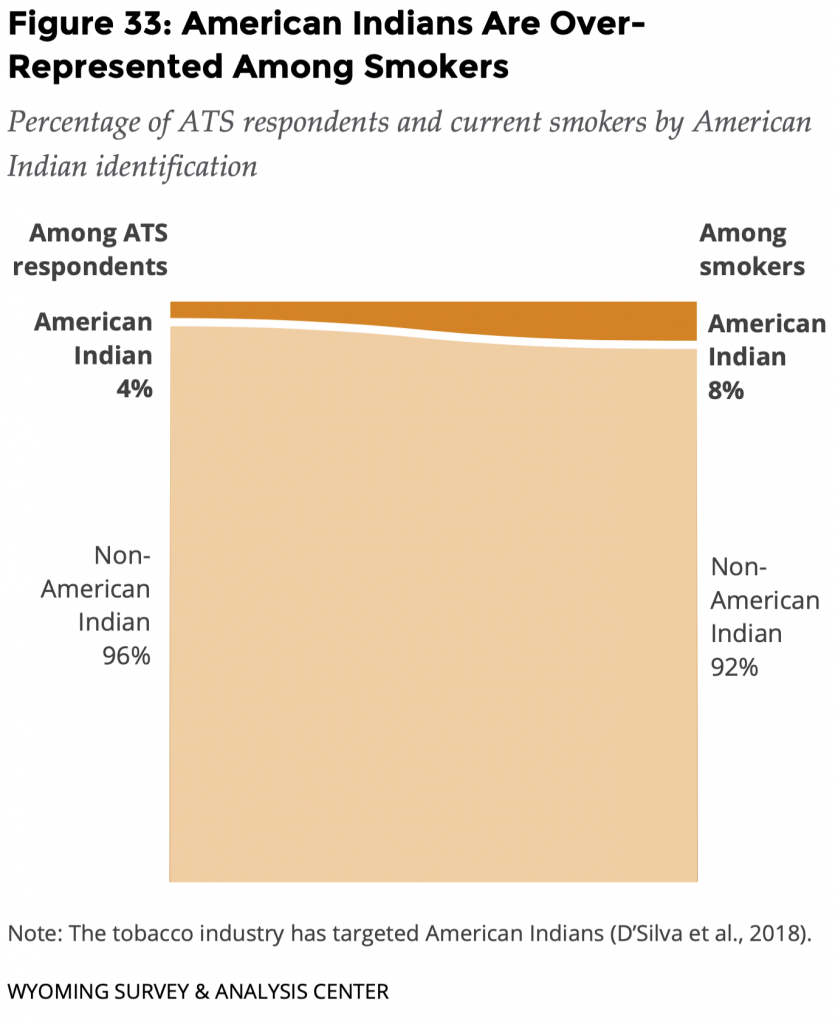

Tobacco companies have long used the ceremonial significance of tobacco to entice American Indians to use their commercial tobacco products (D’Silva et al., 2018). Tobacco companies have a history of targeting this community, beginning with using American Indian imagery and symbols in marketing, often depicting negative stereotypes. Changing their approach, tobacco companies began to shift their branding appearing to uphold the spiritual use of ceremonial tobacco by American Indians and began to introduce their products as all natural (D’Silva et al., 2018). With tobacco industries using the misrepresentation of American Indian culture and tradition to market their commercial tobacco products, the smoking rate for American Indians is much higher than the non-American Indian population.

WYSAC considered respondents American Indian when they self-identified as American Indian or multiracial including American Indian, regardless of whether they reported Hispanic ethnicity. This approach allowed for a larger sample from which to draw conclusions.

For context, American Indian and Alaska Native people make up 2.7% of the Wyoming population, although that number excludes American Indian and Alaska Natives who identify as more than one race or ethnicity including Hispanic or Latinx (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019).

A key limitation of the ATS is that it does not specifically account for ceremonial use of tobacco products. Asking about specific commercial products may lead respondents to exclude ceremonial use on their own.

Smoking

About twice the percentage of adults who identified as American Indian smoked cigarettes (24%).

About twice the percentage of adults who identified as American Indian smoked cigarettes (24%).

Adults who identified as American Indian are over-represented among smokers (Figure 33). Only 4% of adults who responded to the survey were American Indian, yet they made up 8% of current smokers in the survey.

Current Smokers’ Quit Attempts: Lifetime and Past Year

Even after expanding the population analyzed as American Indians, fewer than 50 current smokers said they were American Indians. That is insufficient data for a precise estimate of lifetime and past year quit attempts in this report. WYSAC is available to discuss the data and associated limitations with interested parties.

Exposure to SHS at Work

Due in part to the small sample size for the American Indian population, the difference between reports of SHS exposure was not statistically significant.

- 31% of American Indian adults reported that they were exposed to SHS at their workplace.

- 21% of non-American Indian adults reported that they were exposed to SHS at their workplace.

Behavioral Health

Historically, the tobacco industry has targeted people experiencing behavioral health conditions (such as depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, substance use disorder, and psychotic disorder; Williams et al., 2013). Tobacco retailers are also more common in neighborhoods where people with behavioral health conditions live (Young-Wolff et al., 2014). This may be due in part to the overlap between people with behavioral health conditions and lower incomes.

Further, people experiencing behavioral health issues often have fewer resources to help them quit using tobacco (Williams et al., 2013). Research has shown that in a behavioral health setting, patients who are addicted to nicotine are less likely to be treated for a tobacco addiction than for addictions to alcohol or other substances (Petersen, 2003).

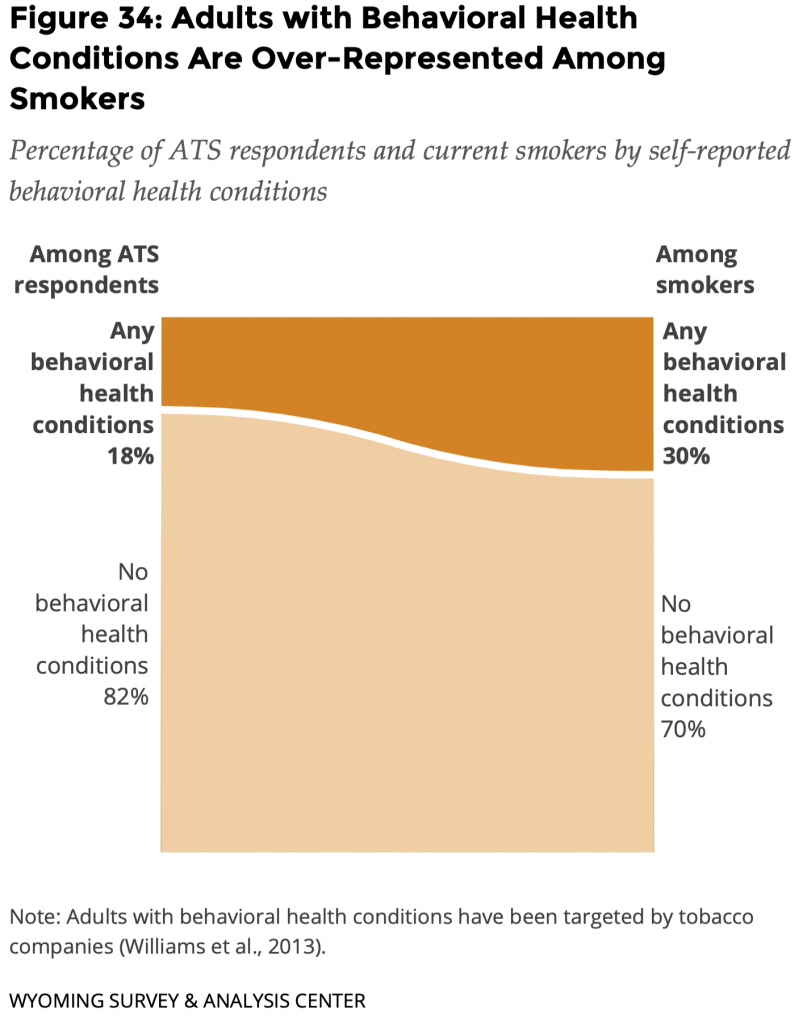

For all these reasons, studies (such as CDC, 2013; Talati et al., 2016) have demonstrated an association between cigarette smoking and behavioral health conditions. People with behavioral health conditions are more likely to smoke, and smokers with these conditions tend to smoke more cigarettes than smokers without behavioral health conditions (CDC, 2013). The 2019 ATS asked respondents “Do you have any mental [behavioral] health conditions, such as anxiety disorder, depression disorder, bipolar disorder, alcohol abuse, drug abuse, or schizophrenia?” About one fifth (18%) of adults reported having at least one behavioral health condition.

For context, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health showed that about 23% of adults in Wyoming have behavioral health conditions (SAMHSA, 2021).

As with any self-report data, it is possible that people under-reported health conditions on the ATS, especially those conditions that may have stigma attached such as behavioral health conditions.

Smoking

About twice the percentage of adults who said they had at least one behavioral health condition smoked cigarettes (21%).

About twice the percentage of adults who said they had at least one behavioral health condition smoked cigarettes (21%).

Adults with behavioral health conditions are over-represented among smokers (Figure 34). Only 18% of adults who responded to the survey reported having behavioral health conditions, yet they made up 30% of current smokers in the survey.

Current Smokers’ Quit Attempts: Lifetime and Past Year

Due in part to the small sample size for people with behavioral health conditions, the differences between lifetime quit attempts for smokers with behavioral health conditions and those without behavioral health conditions were not statistically significant.

- 82% of current smokers with behavioral health conditions had stopped smoking for at least one day because they were trying to quit for good, and

- 81% of current smokers without behavioral health conditions had stopped smoking for at least one day because they were trying to quit for good.

Due in part to the small sample size for people with behavioral health conditions, the differences between recent quit attempts for smokers with behavioral health conditions and those without behavioral health conditions were not statistically significant.

- 48% of current smokers with behavioral health conditions had tried to quit smoking at least once in the past year, and

- 36% of current smokers without behavioral health conditions had tried to quit smoking at least once in the past year.

Smokers’ Obstacles to Quitting Smoking Cigarettes

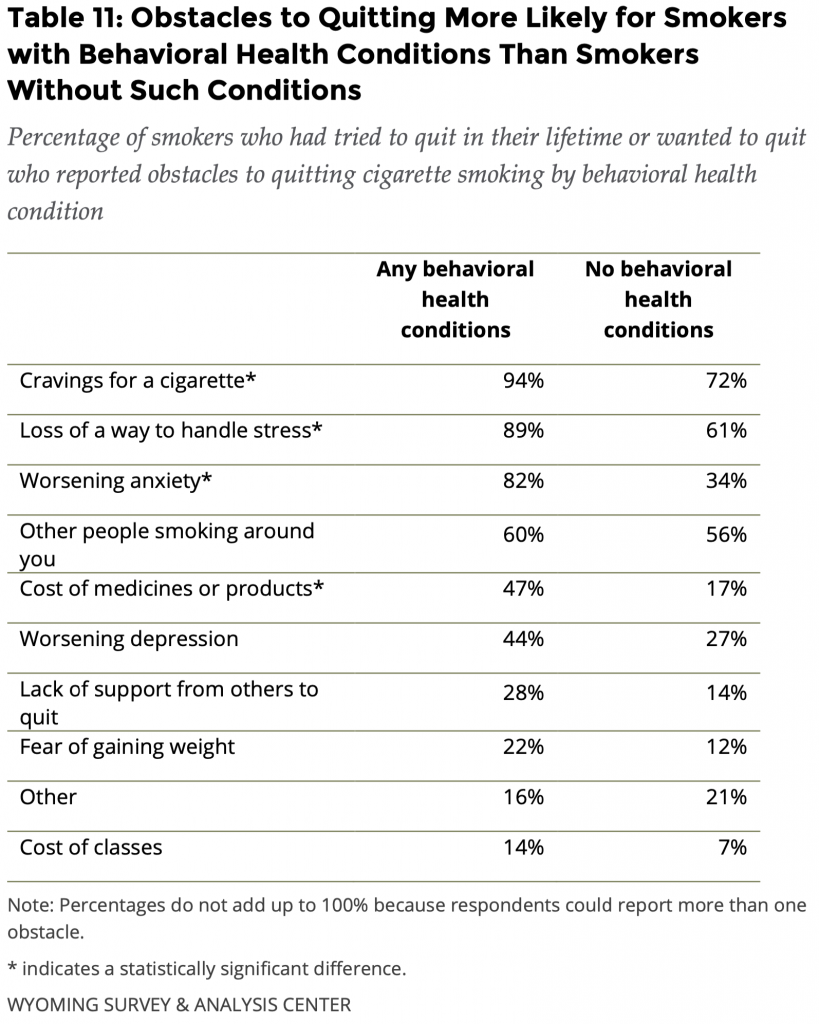

Four obstacles to quitting were statistically significantly more common among people with behavioral health conditions (Table 11). The Wyoming Quit Tobacco (WQT) program is designed to address the common barriers that adults face when quitting smoking, including these four obstacles.

Four obstacles to quitting were statistically significantly more common among people with behavioral health conditions (Table 11). The Wyoming Quit Tobacco (WQT) program is designed to address the common barriers that adults face when quitting smoking, including these four obstacles.

Craving cigarettes was the greatest obstacle for the majority of current smokers who had tried to quit. It was a more common obstacle for current smokers with behavioral health conditions (94%) than it was for those without behavioral health conditions (72%).

Current smokers with behavioral health conditions said other obstacles to quitting cigarettes included the loss of a way to handle stress (89%) and worsening anxiety (82%). Just under half (47%) of current smokers with behavioral health conditions said the cost of medicines or products was an obstacle to quitting, but 17% of current smokers without behavioral health conditions said this was a barrier to quitting. It is possible that an intersection exists between behavioral health conditions and lower incomes, but too few people in these groups were in the ATS sample to do any analyses.

Exposure to SHS at Work

Due in part to the small sample size of people who reported behavioral health conditions, the difference between reports of SHS exposure was not statistically significant.

- 24% of adults with behavioral health conditions reported that they were exposed to SHS at their workplace.

- 21% of adults without behavioral health conditions reported that they were exposed to SHS at their workplace.

Young Adults

ATS data (see the Goal Area 1: Preventing Initiation of Tobacco Use section) shows that most smokers start smoking as youths or young adults. Young adulthood is an impressionable stage when people may begin a lifelong smoking habit or a habit begun during adolescence could become set (Biener & Albers, 2004; Lee et al., 2020), making them a priority population. The tobacco industry has targeted young adults with advertising and marketing that promises to help them create the attractive, successful, and popular personas they seek (Farber & Folan, 2017). Industry campaigns promote messages, values, and product features designed specific to young adults (Lee et al., 2020). Tobacco companies place these campaigns in places young adults frequent most, such as colleges, fraternities, and bars (Ling & Glantz, 2002). With such targeted efforts, young adults are a priority population and require equally targeted efforts for tobacco prevention and control strategies.

WYSAC considered respondents young adults when they were between ages 18 and 29 to increase the sample size and improve the reliability of estimates for this group. The U.S. Census Bureau’s public reports do not estimate the proportion of Wyoming’s population within this specific age range. The closest match is people 20 to 29 years old. As such, about 13% of Wyoming adults are between the ages of 20 and 29 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020).

Smoking

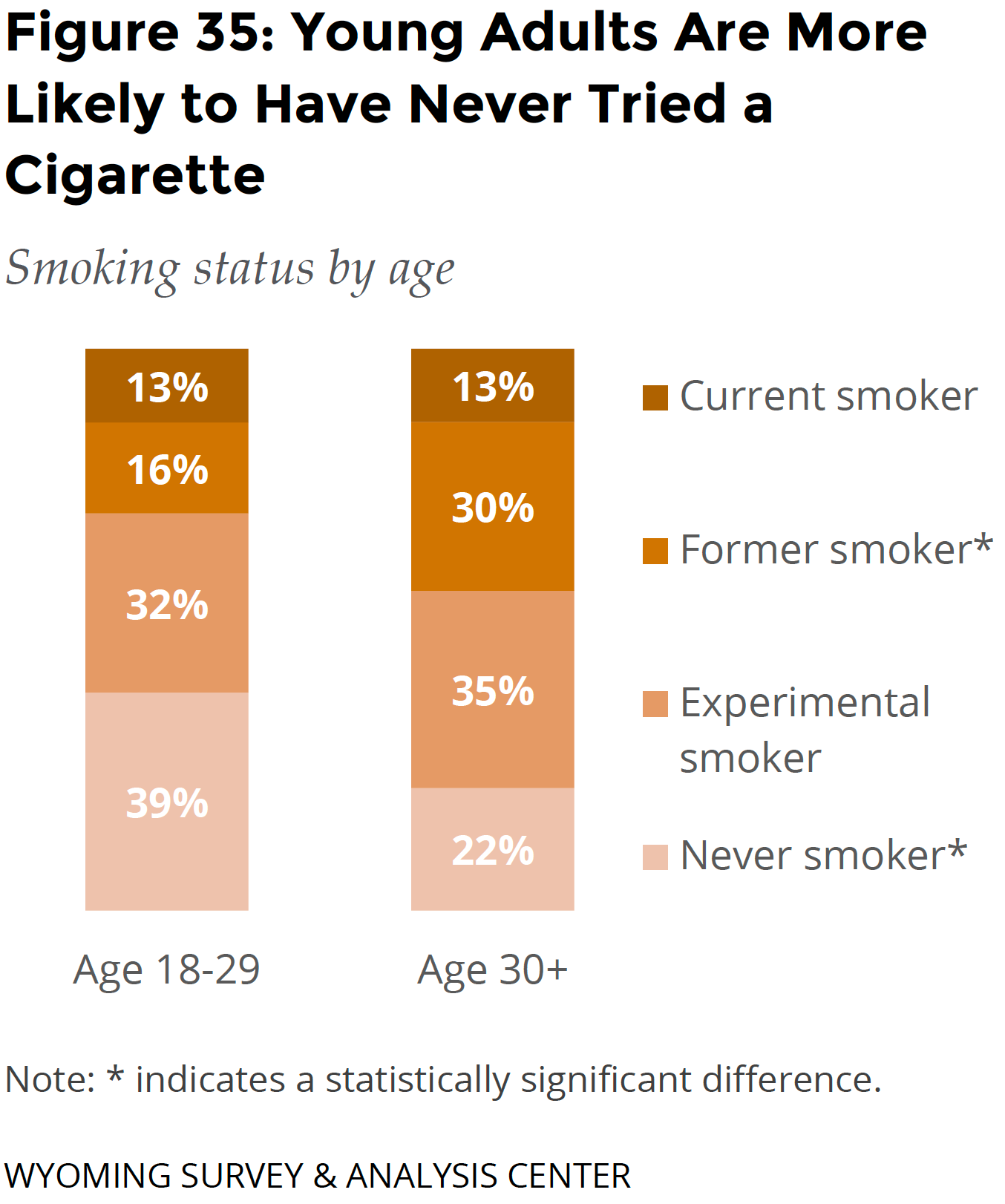

The smoking rate of young adults (13%) was similar to the smoking rate of other adults (13%; Figure 35).

The smoking rate of young adults (13%) was similar to the smoking rate of other adults (13%; Figure 35).

Young adults are more likely to have never tried a cigarette: 39% of young adults have never tried a cigarette as compared to 22% of other adults. Because so few adults begin smoking after the age of 21 (see the Goal Area 1: Preventing Initiation of Tobacco Use section), this difference between age cohorts may indicate that experimentation with tobacco products is becoming less common over time. It may also demonstrate the success of TPCP efforts to curb youth cigarette initiation and use.

Young adults are more likely to use ENDS (12%), which may lead to later initiation of smoking cigarettes. More research is needed to investigate this potential pathway to smoking.

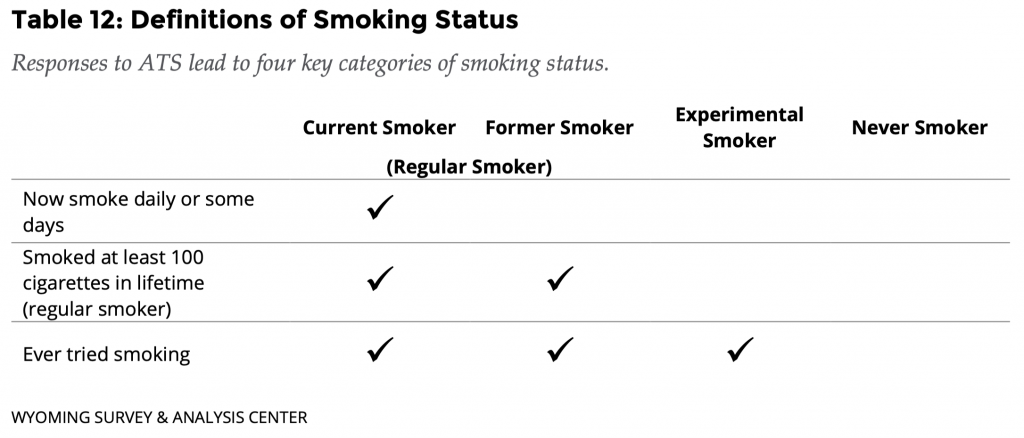

Table 12 details the four categories of smoking status used in Figure 35.

Current Smokers’ Quit Attempts: Lifetime and Past Year

Fewer than 50 current smokers said they were between 18 and 29 years old. That is insufficient data for a precise estimate in this report. WYSAC is available to discuss the data and associated limitations with interested parties.

Exposure to SHS at Work

Significantly, more young adults were exposed to SHS at their workplace (29%) than other working adults (19%). A possible explanation for this is an occupational disparity, as young adults who work in the service, maintenance, and transportation industries are at a higher risk of exposure to SHS than those working in other industries (Holmes & Ling, 2017). However, the ATS does not collect information about specific occupations.

Conclusions

The 2019 ATS data highlights the impact of the tobacco industry’s targeted efforts to engage already vulnerable populations in tobacco use. The 2019 ATS data shows that people from households who make less than $30,000, who identify as American Indian, or who report having behavioral health conditions are disproportionately affected by tobacco use.

Current smokers with behavioral health conditions are more likely to face four obstacles to quitting than smokers without such conditions: craving cigarettes, the loss of a way to handle stress, worsening anxiety, and the cost of medicines or products. Free coaching and free cessation aids from the WQT program address these obstacles.

Young adults were more likely to have never tried a cigarette compared to other adults. This difference between age cohorts may indicate that experimentation with tobacco products is becoming less common over time, possibly due to the concerted efforts of the TPCP and other organizations to prevent youth use and initiation of cigarettes.

These priority populations are already vulnerable and most demonstrate higher smoking rates. These communities carry disproportionate burdens of smoking. Work related to Goal 4 of the TPCP is essential to combat targeted efforts from the tobacco industry to eliminate these tobacco-related disparities and work toward health equity.

Acknowledgement

Proportion plots adapted from a template distributed by Stephanie Evergreen: https://stephanieevergreen.com/proportion-plots/