Summary

One of the four key goals the Wyoming Tobacco Prevention and Control Program (TPCP) shares with the federal tobacco prevention and control program is to decrease exposure to secondhand smoke (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2017). According to the Surgeon General (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2014) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2014), smokefree policies improve public health by reducing exposure to secondhand smoke. By enacting and implementing smokefree indoor air policies and laws, Wyoming communities reduce exposure to secondhand smoke and, ultimately, can reduce tobacco-related economic costs, disease, and death (CDC, 2017).

Smokefree indoor air laws also contribute to social norms against smoking and reduce cigarette consumption and related health problems (CDC, 2014; USDHHS, 2014). Independent, high-quality research uniformly shows that smokefree laws do not result in net negative economic impacts (Loomis, Shafer, & van Hasselt, 2013; Scollo, Lal, Hyland, & Glantz, 2003; USDHHS, 2006)

Effects of Smokefree Indoor Air Laws in Wyoming

In 2009, WYSAC compared towns in Wyoming with comprehensive smokefree indoor air laws to similar towns in Wyoming without comprehensive smokefree indoor air laws. The analyses examined the effect of these laws on attitudes toward tobacco use and smoking behaviors among youth and adults. The full report, including a description of the comparison towns, is available at https://wysac.uwyo.edu/wyomingtobacco/.

In 2009, WYSAC compared towns in Wyoming with comprehensive smokefree indoor air laws to similar towns in Wyoming without comprehensive smokefree indoor air laws. The analyses examined the effect of these laws on attitudes toward tobacco use and smoking behaviors among youth and adults. The full report, including a description of the comparison towns, is available at https://wysac.uwyo.edu/wyomingtobacco/.

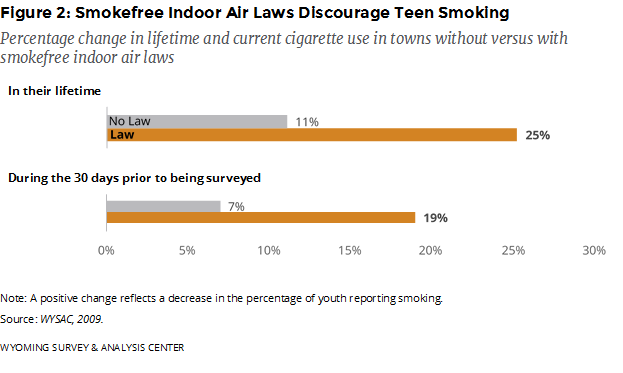

The 2009 smokefree indoor air laws were associated with greater shifts toward anti-smoking attitudes among youth and greater reductions in youth smoking prevalence when compared to towns without smokefree indoor air laws (Figure 1).

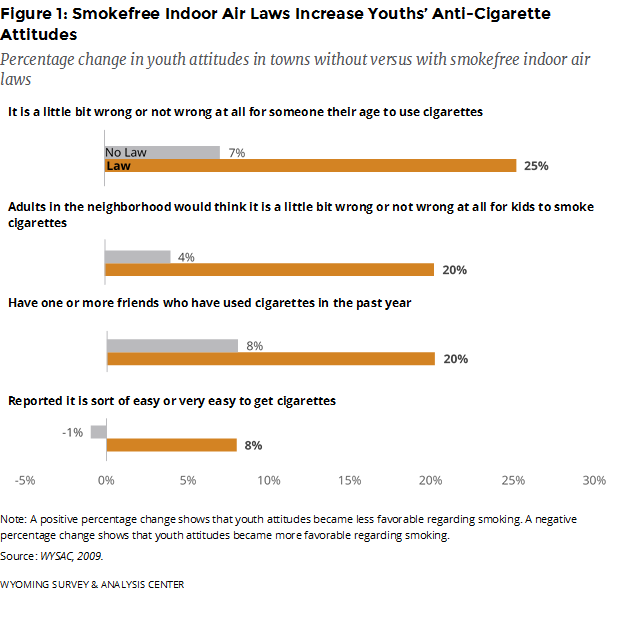

There were also greater reductions in smoking prevalence for youth in towns with comprehensive smokefree indoor air laws compared to youth in towns without such laws (Figure 2).

WYSAC’s analysis did not show any statistically significant differences for measured adult attitudes regarding smoking or the percentage of adults who smoked, how much those adults smoked, or those adults’ attempts to quit smoking between Wyoming towns with comprehensive smokefree indoor air laws and comparison towns.

Health Effects

Indicating compliance with smokefree air laws, studies show that youth and adults who live in towns with smokefree indoor air laws are less likely to report exposure to secondhand smoke in restaurants than youth and adults who live in towns without smokefree indoor air laws. They are also less likely to report respiratory health problems associated with tobacco smoke (Callinan et al., 2016; Cance, Talley, & Fromme, 2015; Guide to Community Preventive Services, 2015; Lin, Park, & Seo, 2015).

Overall, exposure to secondhand smoke increases the risk of heart attacks (medically described as acute myocardial infarction). Diseases of the heart, such as heart attacks, are the leading cause of death in Wyoming (CDC, National Center for Health Statistics, 2017). Meyers, Neuberger, & He (2009) conducted a literature review and meta-analysis of studies published between 2004 and 2009 and found that smokefree indoor air policies protect the public fromheart attacks. Data from towns (including Helena, Montana, and Pueblo, Colorado) also show that smokefree indoor air laws decrease this risk. Young people and nonsmokers benefit the most from this effect. Myers and colleagues noted that the laws have short-term effects, but it may take years to show their full effects. Vander Weg, Rosenthal, and Vaughn Sarrazin (2012) examined the effects of local and state-level smokefree indoor air laws covering restaurants, bars, and workplaces passed in the United States between 1991 and 2008. They focused on the hospitalizations of Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 and older. In the three years after the laws went into effect, hospital admission rates for heart attacks fell.

Hahn (2010) conducted a literature review covering work published in the first decade of the 21st century. She found that comprehensive smokefree air laws “improve the health of hospitality workers and the general population by improving indoor air quality, reducing [heart attacks and asthma problems,] and improving infant and birth outcomes” (p. S66); additional outcomes included smaller percentages of people who smoked, smokers smoking less, and smokers having more success quitting smoking.

Mackay, Irfan, Haw, and Pell (2010) pooled data from 17 studies and found strong evidence that smokefree air laws reduce the risk of heart attack in those communities, and that this protection increases over time. In a prestigious Cochrane Review, Callinan, Clarke, Doherty, and Kelleher (2010) found that smokefree air laws reduced exposure to secondhand smoke in public places, especially for people working in restaurants, bars, and other hospitality workplaces. These findings are consistent with CDC’s logic models.

One potential unintended consequence of smokefree air policies covering public places is moving that smoking to homes, potentially around children. Callinan et al. (2010) found no evidence for such a shift in their review of published studies. This finding was replicated in a study conducted by McGeary, Dave, Lipton, and Roeper (2017). On the contrary, McGeary et al., like some of the studies reviewed by Callinan et al., found reductions in exposure to secondhand smoke at home after laws covering public places were enacted.

Collectively, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD) and other lower respiratory diseases are the fourth leading cause of death in Wyoming (CDC, National Center for Health Statistics, 2017). Hahn, Rayens, Adkins, Simpson, and Frazier (2014) compared data from regions in Kentucky that had municipal smokefree indoor air laws to regions that did not have such laws. They found that people living in towns with comprehensive laws had a 22% reduced risk of hospitalization for COPD compared to people living in towns with non-comprehensive laws or no laws at all. Vander Weg and colleagues (2012) found that Medicare-billed hospital admission rates for COPD fell by 15% in the first three years after implementing comprehensive smokefree indoor air laws.

Economic Effects of Smokefree Indoor Air Laws

Loomis, Shafer, and van Hasselt (2013) examined the economic impact of smokefree laws in the United States and found that smokefree laws have little or no effect on economic outcomes in restaurants and bars. Furthermore, they found that smokefree laws improve employment and health. After implementation of smokefree laws in West Virginia, restaurant employment increased by a statistically significant 1%. In 2010, Boles, Dilley, Maher, Boysun, and Reid found that a statewide smokefree air law in Washington State was connected with a greater-than-expected revenue increase for bars and taverns.

Scollo and colleagues conducted three literature reviews (Scollo & Lal, 2005, 2008; Scollo et al., 2003) on the economic effect of smokefree indoor air laws. To assess the quality of this research, they used Siegel’s (1992) four criteria for identifying high-quality studies of economic impacts of smokefree indoor air laws:

1. Using objective data (e.g., tax receipts or employment statistics),

2. Including all data points after the law was implemented and data for several years before,

3. Using statistical methods that control for trends and random fluctuation in the data, and

4. Accounting for overall economic trends.

Scollo and colleagues (Scollo & Lal, 2005, 2008; Scollo et al., 2003) found no peer-reviewed, published, independent study that showed a negative economic impact from the implementation of smokefree indoor air laws. Studies asserting a negative economic impact often had the following characteristics (Scollo & Lal, 2005):

- Data were based on subjective impressions or estimates of anticipated change rather than on objective, verified, or audited data.

- Data did not account for an adequate period before and after the law went into effect to establish underlying trends.

- Funding came from the tobacco industry or organizations allied with the tobacco industry.

- The studies were not published in scientific journals.

The 2006 Surgeon General’s report (USDHHS, 2006) also examined numerous studies of state and local smokefree laws: “Evidence from peer-reviewed studies shows that smokefree policies and regulations do not have an adverse economic impact on the hospitality industry” (p. 16).

Most recently, Hopkins, Leeks, Kaira, Chattopadhyay, and Soler (2010) also reviewed the published literature and found that smokefree air laws reduce tobacco use and identified four studies that showed economic benefits from smokefree policies in the workplace.

References

Boles, M., Dilley, J., Maher, J. E., Boysun, M. J., & Reid, T. (2010). Smoke-free law associated with higher-than-expected taxable retail sales for bars and taverns in Washington State. Preventing Chronic Disease, 7(4), A79. Retrieved January 3, 2018, from https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2010/Jul/09_0187.htm

Callinan, F. K., McHugh, J., van Baarsel, S., Clarke, A., Doherty, K., & Kelleher, C. (2016). Legislative smoking bans for reducing harms from secondhand smoke exposure, smoking prevalence and tobacco consumption (review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005992.pub3.

Cance, J. D., Talley, A. E., & Fromme, K. (2015). The impact of a city-wide indoor smoking ban on smoking and drinking behaviors across emerging adulthood. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 18(2), 1–9. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv050

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Best practices for comprehensive tobacco control programs–2014. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health promotion, Office on Smoking and Health.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). Eliminating exposure to secondhand smoke: Outcome indicators for comprehensive tobacco control programs–2017. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics [Data File 1999–2016]. (2017). Underlying cause of death 1999–2016. Retrieved January 3, 2018, from http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html

Guide to Community Preventive Services. (2015). Reducing tobacco use and secondhand smoke exposure. Retrieved March 11, 2015, from http://www.thecommunityguide.org/tobacco /index.html

Hahn, E. J. (2010). Smokefree legislation: A review of health and outcomes research. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 39(6, Supplement 1), S66–S76. doi 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.08.013.

Hahn, E. J., Rayens, M. K., Adkins, S., Simpson, N., & Frazier, S. (2014). Fewer hospitalizations for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in communities with smoke-free public policies. American Journal of Public Health, 104(6), 1059–1065. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301887)

Hopkins, D. P., Razi, S., Leeks, K. D., Priya Kalra, G., Chattopadhyay, S. K., Soler, R. E. (2010). Smokefree policies to reduce tobacco use: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 38(2 Suppl.), S275–S289. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.10.029

Lin, H., Park, J., & Seo, D. (2015). Comprehensive US statewide smoke-free indoor air legislation and secondhand smoke exposure, asthma prevalence, and related doctor visits: 2007–2011. American Journal of Public Health, 105(8), 1617–1622. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302596

Loomis, B. R., Shafer, P. R., & van Hasselt, M. (2013). The economic impact of smokefree laws on restaurants and bars in 9 states. Preventing Chronic Disease, 10, 1–8. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd10.120327

Mackay, D. F., Irfan, M. O., Haw, S., & Pell, J. P. (2010). Meta-analysis of the effect of comprehensive smoke-free legislation on acute coronary events. Heart, 96(19), 1525–1530. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.199026

McGeary, K. A., Dave, D. M., Lipton, B. J., Roeper, T. (2017). Impact of smoking bans on the health of infants and children (National Bureau of Economic Research [NBER] Working Paper No. 23995). Retrieved December 7, 2017, from http://www.nber.org/papers/w23995.

Meyers, D. G., Neuberger, J. S., & He, J. (2009). Cardiovascular effect of bans on smoking in public places: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 54(14), 1249–1255. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2009.07.022.

Scollo, M., & Lal, A. (2005). Summary of studies assessing the impact of smoking restrictions on the hospitality industry: Includes studies produced to July 2005. Retrieved June 7, 2012, from http://www.vctc.org.au/tc-res/Hospitalitysummary.pdf

Scollo, M., & Lal, A. (2008). Summary of studies assessing the economic impact of smokefree policies in the hospitality industry: Includes studies produced to 31 January 2008. Melbourne, Australia: Vic Centre for Tobacco Control, the Cancer Council Victoria.

Scollo, M., Lal, A., Hyland, A., & Glantz, S. (2003). Review of the quality of studies on the economic effects of smokefree policies on the hospitality industry. Tobacco Control, 12, 13–20. Retrieved January 16, 2008, from http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/12/1/13 .full.pdf+html?maxtoshow=&HITS=10&hits=10&RESULTFORMAT=&author1=scollo&andorexactfulltext=and&searchid=1&FIRSTINDEX=0&sortspec=relevance&resourcetype=HWCIT

Siegel, M. (1992). Economic impact of 100% smokefree restaurant ordinances. In Smoking and restaurants: A guide for policymakers. Retrieved January 16, 2008, from http://tobaccodocuments.org/lor/87604525-4587.html?pattern=&ocr_position=&rotation=0&zoom=750&start_page=1&end_page=59

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2006). The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coordinating Center for Health Promotion, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2014). The health consequences of smoking – 50 years of progress: A report of the Surgeon General. Retrieved January 21, 2014, from http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/50th-anniversary/index.htm

Vander Weg, M. W., Rosenthal, G. E., & Vaughn Sarrazin, M. (2012). Smoking bans linked to lower hospitalizations for heart attacks and lung disease among Medicare beneficiaries. Health Affairs, 31(12), 2699–2707. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0385

WYSAC. (2009). An expanded analysis of the impact of smokefree ordinances in Wyoming: A preliminary evaluation of the economic, health, and social impacts, by N. M. Nelson, E. Canen, L. L. Feldman, M. Leonardson, & R. Jenniges. (WYSAC Technical Report No. CHES-904). Laramie, WY: Wyoming Survey & Analysis Center, University of Wyoming.