Background

The Wyoming Quit Tobacco Program (WQTP) assists enrollees in their efforts to quit using tobacco products by offering free Quitline phone coaching, free nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), and free or reduced-price prescription (Rx) medications. In the middle of February 2016, the WQTP began offering free Chantix (one of the prescription medications) to enrollees.

The Wyoming Quit Tobacco Program (WQTP) assists enrollees in their efforts to quit using tobacco products by offering free Quitline phone coaching, free nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), and free or reduced-price prescription (Rx) medications. In the middle of February 2016, the WQTP began offering free Chantix (one of the prescription medications) to enrollees.

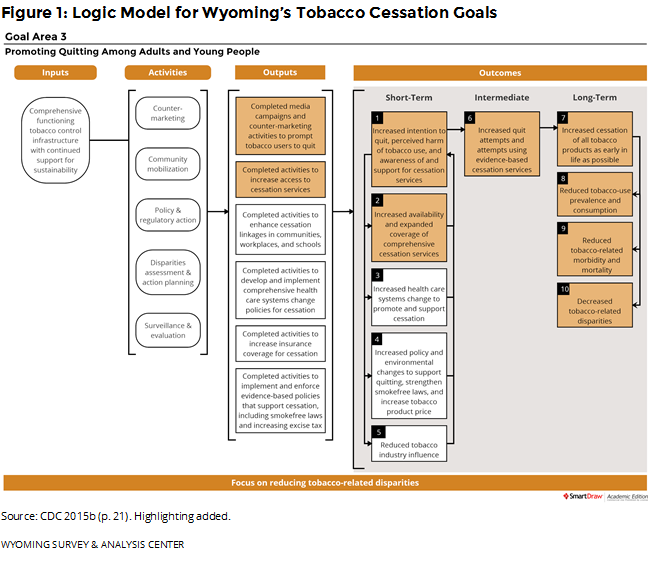

Providing cessation services to Wyoming residents is an important part of the state’s Tobacco Prevention and Control Program (TPCP). Wyoming follows the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines for state tobacco prevention programs (CDC, 2015b). Figure 1 shows how the WQTP and the data presented in this report fit into the goals of Wyoming’s TPCP, with highlighted boxes showing the most relevant parts of CDC’s logic model for cessation.

Under contract to the Wyoming Department of Health, Public Health Division, the Wyoming Survey & Analysis Center (WYSAC) at the University of Wyoming conducts monthly surveys of WQTP enrollees to assess quit rates and enrollee satisfaction. The survey also assesses enrollees’ use of Quitline coaching, NRTs, or prescription medications and enrollees’ opinions of different program elements. This report includes data on WQTP participants surveyed between July and December 2016, seven months after they enrolled in the WQTP. These participants enrolled in the WQTP between December 2015 and May 2016. During this period, National Jewish Health provided WQTP services in Wyoming.

Enrollee Information

Enrollee Information

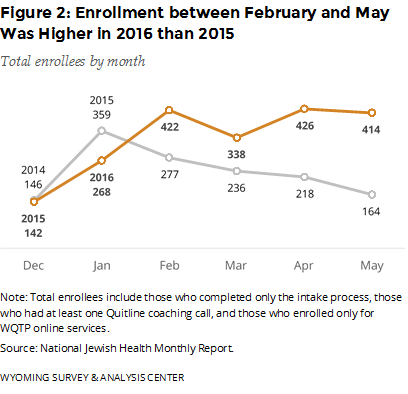

How many people did WQTP serve between December 2015 and May 2016? Figure 2 provides the monthly enrollment for December 2015 – May 2016. For comparison, this figure also shows the same months from the previous year. Enrollees may sign up by completing an intake survey online or by phone. The number of enrollments in January 2016 was unusually low. However, the enrollment between February and May was higher in 2016 than in 2015. This increase coincides with the offer of free Chantix for enrollees, which began in mid-February 2016. Meanwhile, the Wyoming TPCP ran a “Quit It” media campaign in January, February, and March 2016 and advertised free Chantix from mid-April to the end of September 2016. The CDC also ran a 20-week “Tips From Former Smokers” media campaign in 2015 (launched March 30, 2015; CDC, 2015a) and 2016 (launched January 25, 2016; CDC, 2016). Overall, the WQTP enrolled 610 more participants between December 2015 and May 2016 (2,010 enrollees in total) than the same months from the previous year (1,400 enrollees in total).

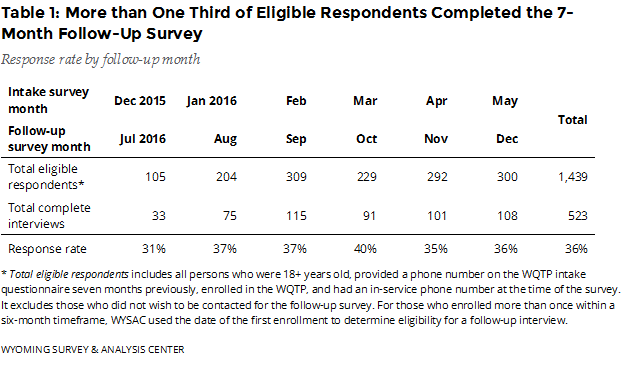

How many enrollees completed the follow-up survey? The July–December 2016 follow-up survey data include responses from 523 completed interviews (Table 1), a 36% response rate.

How many enrollees completed the follow-up survey? The July–December 2016 follow-up survey data include responses from 523 completed interviews (Table 1), a 36% response rate.

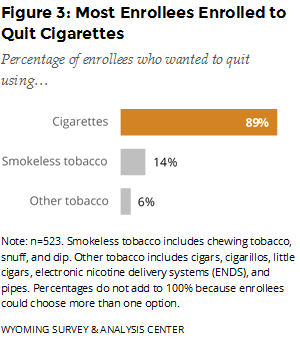

Which type of tobacco products did enrollees want help quitting? Enrollees could choose more than one option, but almost nine out of 10 enrolled in the WQTP to get help with quitting cigarettes (Figure 3).

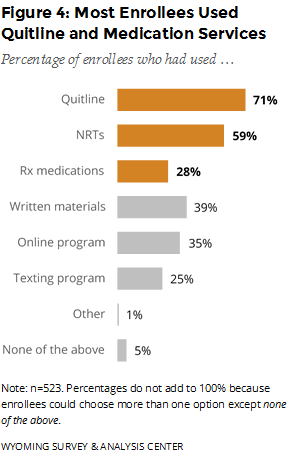

Which program components were enrollees most likely to use? The Quitline was the most commonly used of the three major program components (Quitline, NRTs, and prescription medications; Figure 4). Most enrollees used NRTs, which are mailed to enrollees’ homes for free. Enrollees can order NRTs by going through the Quitline phone coaching or the online support program.

In mid-February 2016, the WQTP began offering free Chantix to enrollees. This report includes data from people who enrolled before and after this programming change. (See Special Section: Free Chantix and the WQTP for details related to the offer of free Chantix.) Enrollees can order prescription medications only by going through the Quitline phone coaching. Over one quarter of enrollees used prescription medications such as Chantix. Prescription medications, which require a prescription from a physician, were the least commonly used of the three major components.

In mid-February 2016, the WQTP began offering free Chantix to enrollees. This report includes data from people who enrolled before and after this programming change. (See Special Section: Free Chantix and the WQTP for details related to the offer of free Chantix.) Enrollees can order prescription medications only by going through the Quitline phone coaching. Over one quarter of enrollees used prescription medications such as Chantix. Prescription medications, which require a prescription from a physician, were the least commonly used of the three major components.

Relatively few enrollees, 26 (5%), reported not using any program component (i.e., none of the above). These enrollees may have completed the intake questionnaire without participating in any other program component. Because these responses are self-reported, respondents’ perspectives or memories about using the program may differ from National Jewish Health’s administrative records. Still, these enrollees form a useful comparison group for gauging the effectiveness of different program components.

WQTP Outcomes

WQTP Outcomes

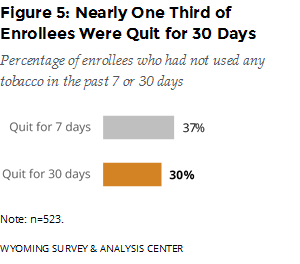

Were enrollees successful in their cessation effort? The follow-up survey asked enrollees if they had used any tobacco products in the previous seven days. If they had not, the survey asked if they had used any tobacco products in the previous 30 days. For this six-month period, 37% of enrollees were quit for seven days; 30% were quit for 30 days (Figure 5).

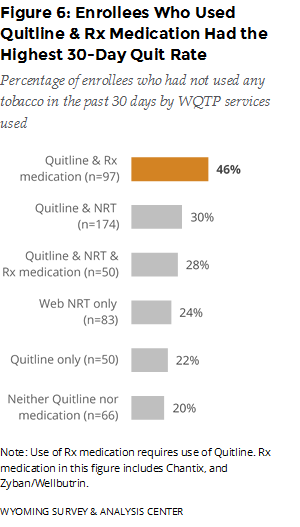

Which program component was most effective? The best outcome was associated with those who used both Quitline coaching and prescription medications. These enrollees had the highest 30-day quit rate (46%), seven months after enrollment (Figure 6).

Few enrollees use prescription medications other than Chantix. A separate WQTP Follow-Up Survey item asked, “Since you enrolled in the Wyoming Quit Tobacco Program, have you used any of the following prescription medications?” Unless they said none of the above, enrollees could choose more than one option for this question. Relatively few enrollees, 27, reported using bupropion (including the specific brands Zyban and Wellbutrin), compared to 146 enrollees who reported using Chantix.

Few enrollees use prescription medications other than Chantix. A separate WQTP Follow-Up Survey item asked, “Since you enrolled in the Wyoming Quit Tobacco Program, have you used any of the following prescription medications?” Unless they said none of the above, enrollees could choose more than one option for this question. Relatively few enrollees, 27, reported using bupropion (including the specific brands Zyban and Wellbutrin), compared to 146 enrollees who reported using Chantix.

WQTP enrollees are a unique subpopulation of Wyoming tobacco users trying to quit. They are more likely to be successful in quitting than the broader population of Wyoming tobacco users. As a reference point, only 8% of Wyoming cigarette smokers have successfully quit without enrolling in the WQTP or using other cessation aids. That is, of those who have smoked in the past 6 months and made a recent quit attempt for 24 hours or longer without using any cessation aids, 8% were abstinent from cigarettes for at least 30 days at the time of the survey (WYSAC, 2017). Compared to Wyoming cigarette smokers who made a recent quit attempt without using any cessation aids, WQTP enrollees who did not use the core program components were approximately 2.5 times more likely to quit. Using different core components increases that difference. Enrollees who used phone coaching and prescription medications (the most successful group of enrollees) were approximately 5.8 times more likely to quit than Wyoming smokers who made a recent quit attempt without using cessation aids.

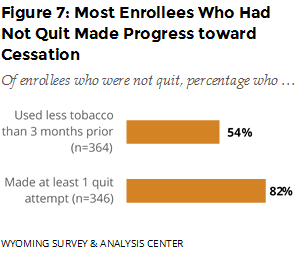

Did those who did not quit make progress toward cessation? WYSAC asked those who had not quit about changes in tobacco consumption and quit attempts (stopping the use of tobacco for 24 hours or longer since enrolling in the WQTP). Over half reported using less tobacco compared to three months prior to the survey, and 82% reported making at least one quit attempt since enrolling (Figure 7).

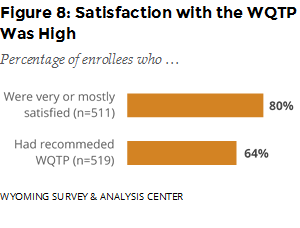

How satisfied were enrollees with the service they received from the WQTP? About one fourth (23%) were mostly satisfied, and 56% were very satisfied with the WQTP. Almost two thirds (64%) reported that they had recommended the program to someone else (Figure 8).

Special Section: Free Chantix and the WQTP

In mid-February 2016, the WQTP expanded its program by offering Chantix at no cost to the enrollees (enrollees were still responsible for covering the cost of a doctor’s visit to obtain the prescription). In mid-April, the Wyoming TPCP began advertising this free Chantix offer (Figure 9). This special section examines the impacts of free Chantix on WQTP enrollment, program component use, and outcomes for those who enrolled between December 2015 and May 2016. WYSAC divided the six months of enrollees into three groups. The first group, participants who enrolled in December 2015 and January 2016, are participants who did not enroll when free Chantix was an option. The second group, participants who enrolled in February and March 2016, was identified to account for the mid-month launch of the offer, any logistical issues that may have arisen during the first two months of the free Chantix program, and delay between the offer of free Chantix and people knowing about the offer (e.g., the mid-April launch date for related media). The third group, participants who enrolled in April and May 2016, enrolled when the offer was fully in place and being actively advertised. Figures in this special section show estimates for WQTP enrollees in each of these three groups.

Enrollment

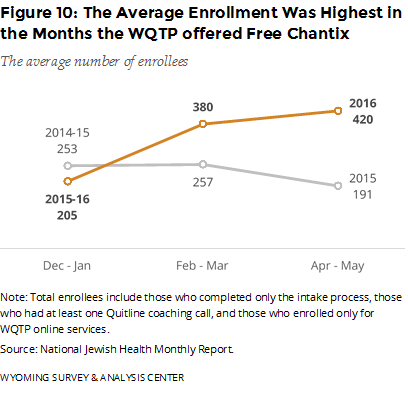

Did the offer of free Chantix affect enrollment? Figure 10 shows the average number of enrollments for the three groups. The relatively high enrollment in WQTP from February through May 2016 coincides with the offer of free Chantix. On average, the enrollment for these months in 2016 was higher than the previous year. Additionally, the media used to promote the free Chantix program, and thus the WQTP (starting in mid-April 2016), coincides with sustained high enrollment, unlike the previous year. We cannot determine how much of the change in enrollment is the result of the free Chantix, general WQTP promotional media, media promoting the free Chantix, or other promotions such as the CDC Tips campaign or word of mouth.

Did the offer of free Chantix affect enrollment? Figure 10 shows the average number of enrollments for the three groups. The relatively high enrollment in WQTP from February through May 2016 coincides with the offer of free Chantix. On average, the enrollment for these months in 2016 was higher than the previous year. Additionally, the media used to promote the free Chantix program, and thus the WQTP (starting in mid-April 2016), coincides with sustained high enrollment, unlike the previous year. We cannot determine how much of the change in enrollment is the result of the free Chantix, general WQTP promotional media, media promoting the free Chantix, or other promotions such as the CDC Tips campaign or word of mouth.

Component Use

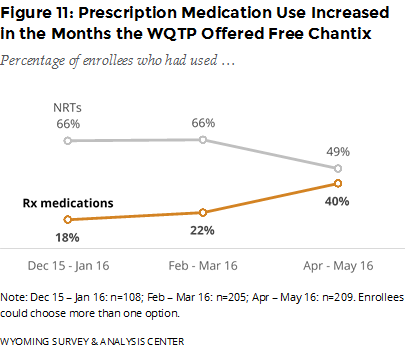

Did the offer of free Chantix affect the use of WQTP components? During the six-month period described in this report, the use of prescription medications such as Chantix increased after the WQTP started offering free Chantix. Simultaneously, the use of NRTs decreased (Figure 11). This shift was relatively slight in the first two months of offering free Chantix and greater in the last two months of data.

Did the offer of free Chantix affect the use of WQTP components? During the six-month period described in this report, the use of prescription medications such as Chantix increased after the WQTP started offering free Chantix. Simultaneously, the use of NRTs decreased (Figure 11). This shift was relatively slight in the first two months of offering free Chantix and greater in the last two months of data.

It is reasonable to tie the increased use of prescription medications to the offering of free Chantix (relatively few enrollees used other prescription medications). It may also be that people opted for Chantix instead of NRT when both were free (ignoring the cost of a physician visit to obtain a prescription for Chantix).

Program Success

What is the quit rate for Chantix users? Enrollees (n = 107) who used Chantix (with no other NRTs or Rx medications) had the highest 30-day quit rate (47%). This is compared to those who used Quitline only (22%), those who used NRTs through the online program (24%), and those who used Quitline and NRTs (30%).

Did the effectiveness of Chantix improve the overall quit rate? Although Chantix users usually have a relatively high quit rate, overall program quit rate does not seem to depend on the status of free Chantix. The overall quit rates for the two months before offering free Chantix (30%), the first two months of the offer (27%), and the last two months of data (33%) are all fairly similar. Overall program satisfaction was also fairly stable across the three time periods.

Priority Populations

In addition to overall outcomes, this report provides follow-up data on four priority populations: those who used alternative nicotine products (such as electronic nicotine delivery systems [ENDS]), those who reported mental health conditions, those who participated in the pregnancy program, and those who participated in the American Indian Commercial Tobacco Program (AICTP).

Alternative Nicotine Product Users

ENDS—such as e-cigarettes, e-hookahs, and vape pens—are battery-operated devices that simulate smoking but do not involve the burning of tobacco. The heated aerosol produced by ENDS often contains nicotine and comes in different flavors.

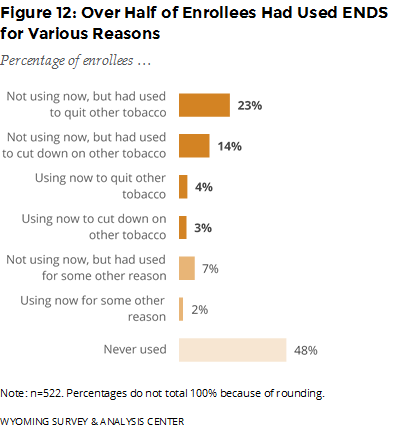

Have enrollees ever used ENDS or other similar nicotine products? If so, why did they use them? Over half (52%) of enrollees had used ENDS in their lifetime (Figure 12). Moreover, 83% of enrollees who had used ENDS used them to quit or cut-down on other tobacco although they are not approved as cessation aids by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA, 2016).

Only two enrollees had used another alternative nicotine product (such as Nicogel, orbs, or Camel strips) that is not approved as a smoking cessation product.

Only two enrollees had used another alternative nicotine product (such as Nicogel, orbs, or Camel strips) that is not approved as a smoking cessation product.

Mental Health

Studies (e.g., CDC, 2013; Talati, Keyes, & Hasin, 2016) have demonstrated an association between cigarette smoking and mental health conditions. People with mental health conditions are more likely to smoke and to smoke more cigarettes than people without mental health conditions (CDC, 2013). Based on combined data from the 2009–2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 37% of Wyoming adults who had a mental health condition had smoked part or all of a cigarette within the 30 days prior to being surveyed, compared to 23% of Wyoming adults without a mental health condition (CDC, 2013).

In the intake survey, enrollees answered questions about their mental health. The intake questionnaire asks, “Do you have any mental health conditions, such as anxiety disorder, depression disorder, bipolar disorder, alcohol/drug abuse,3 or schizophrenia?” WYSAC merged responses to this mental health question at intake with the follow-up survey data; 512 follow-up survey respondents had answered the question. Of these respondents, 36% said they had a mental health condition at the time of the intake survey.

In the intake survey, enrollees answered questions about their mental health. The intake questionnaire asks, “Do you have any mental health conditions, such as anxiety disorder, depression disorder, bipolar disorder, alcohol/drug abuse,3 or schizophrenia?” WYSAC merged responses to this mental health question at intake with the follow-up survey data; 512 follow-up survey respondents had answered the question. Of these respondents, 36% said they had a mental health condition at the time of the intake survey.

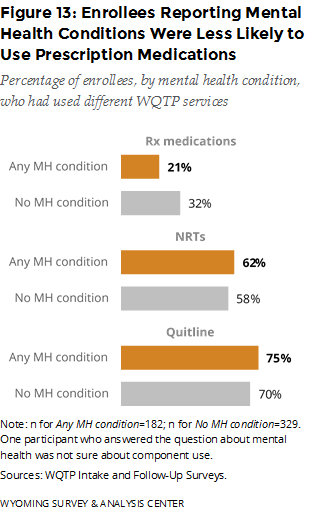

How did key program component usage rates differ for enrollees who reported mental health conditions? Enrollees who reported mental health conditions were less likely to use prescription medications but slightly more likely to use the Quitline and NRTs, compared to those who did not report mental health conditions. (Figure 13).

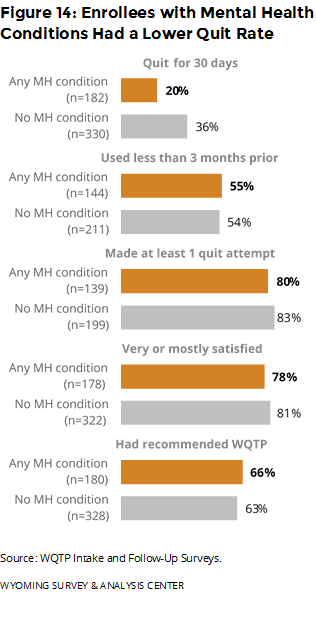

Did outcomes differ for people with mental health conditions? Those with mental health conditions were less likely to have been quit for 30 days, compared to those who did not report such conditions. All other outcomes had only a small difference between enrollees who reported mental health conditions and those who did not report such conditions (Figure 14).

Did outcomes differ for people with mental health conditions? Those with mental health conditions were less likely to have been quit for 30 days, compared to those who did not report such conditions. All other outcomes had only a small difference between enrollees who reported mental health conditions and those who did not report such conditions (Figure 14).

Pregnant Women

Smoking is linked to complications during pregnancy, including miscarriage and birth defects (CDC, 2015c). These excess risks make pregnant women a priority population for the Wyoming TPCP.

Eleven enrollees said they were pregnant at the time of enrollment. None of these enrollees responded to the follow-up survey.

American Indians

On August 1, 2015, National Jewish Health began offering the American Indian Commercial Tobacco Program (AICTP) to provide a culturally-sensitive approach to help American Indians quit commercial tobacco use (National Jewish Health, 2015). One of the seven American Indians who enrolled in the AICTP completed the follow-up survey. The small sample size means that it is not possible to generalize the results to all American Indian enrollees.

Enrollee Reports on Strengths and Weaknesses of the WQTP

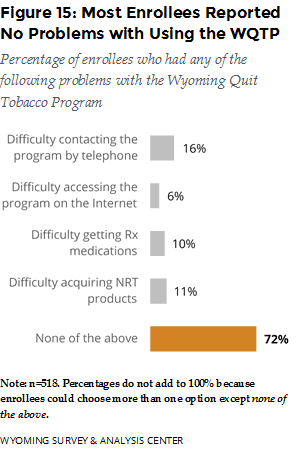

What did enrollees report about the strengths and weaknesses of the WQTP? Most enrollees (72%) reported no problems with using the core program components (Figure 15). Among those who reported difficulty, contacting the program by telephone was the most problematic, followed by acquiring NRT products and prescription medications.

Conclusions

The data for WQTP enrollees who completed the follow-up survey between July and December 2016 (meaning they enrolled between December 2015 and May 2016) show that roughly nine out of 10 program participants enrolled to get help with quitting cigarettes. Most enrollees used the Quitline. In addition, compared to the previous semiannual report (WYSAC, 2016), prescription medication use increased from 17% to 28% while NRT use decreased from 72% to 59%. Detailed analyses indicate that these shifts in program use coincided with the offer of free Chantix beginning in February 2016.

Depending on what core components they use (if any), adults who enroll in the WQTP are about 2.5 to 5.8 times more likely to quit than Wyoming adults who try to quit smoking without enrolling in the WQTP or using other cessation aids, who have an 8% quit rate. Nearly one third (30%) of enrollees reported being quit for at least 30 days. This quit rate is slightly higher than the 30-day quit rate (26%) reported in the previous semiannual report (WYSAC, 2016). Those who used Quitline coaching and any prescription medication (including Chantix and Zyban/Wellbutrin) had the highest 30-day quit rate (46%). The quit rate for enrollees who used Quitline coaching and Chantix—but not Zyban/Wellbutrin—was virtually the same (47%).

Satisfaction with WQTP was high: 80% of enrollees reported being very or mostly satisfied with the program, and the majority (64%) had recommended the WQTP to someone else. Data from the previous semiannual report indicated similar high levels of program satisfaction.

The majority (72%) of respondents reported no problems with the WQTP. Among those who reported difficulty, contacting the program by telephone was the most problematic, followed by acquiring NRT products and prescription medications.

WYSAC analyzed follow-up data for four priority populations: those who used alternative nicotine products such as ENDS, those who reported mental health conditions, those who participated in the pregnancy program, and those who participated in the AICTP. More than half (52%) of enrollees had used ENDS in their lifetime. Of these, 83% had used them to quit or cut-down on other tobacco even though they are not approved as cessation aids by the FDA (2016). Enrollees reporting mental health conditions were less likely to use prescription medications and to be quit for 30 days than those reporting no such conditions. The sample sizes for those in the pregnancy program and the AICTP are too small to draw conclusions about those programs or to generalize to other WQTP enrollees.

The follow-up data show that WQTP program components successfully help enrollees quit. The increased use of these components, especially prescription medications such as Chantix, would likely increase the overall success of the program.