Summary

In the United States, children and teens constitute the majority of all new smokers (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2014). The earlier young people begin using tobacco products, the more likely they are to use them as adults and the longer they will remain users (Institute of Medicine, 2015). Two of the four key goals the Wyoming Tobacco Prevention and Control Program (TPCP) shares with the federal tobacco prevention and control program are to (a) reduce youth initiation of tobacco use (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2014) and (b) promote quitting tobacco use, including among youth (CDC, 2015).

Wyoming’s youth prevalence rates for smoking cigarettes have generally been near the national average, and both have been decreasing. (Comparisons of Wyoming and U.S. rates have not been possible since 2015 because Wyoming stopped participating in the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System [YRBSS].) Most of Wyoming’s 2015 high school smokers had made at least one quit attempt in the past year (YRBSS, 2015).

Wyoming middle and high school students generally perceive smoking cigarettes and smokeless tobacco use as socially unacceptable (Prevention Needs Assessment [PNA], 2016).

Tobacco control programs reduce youth smoking prevalence and susceptibility (youth who have never smoked and are at risk for trying smoking). Tobacco control policies, such as smoke-free air policies and high prices for tobacco products, can decrease the smoking prevalence for youth and, in time, contribute to a lower adult smoking prevalence, thereby reducing health problems associated with smoking (Singh, et al., 2016).

Age of Initiation: Young Smokers

Youth who have never smoked can be identified as susceptible to smoking based on their estimated likelihood of smoking. Farrelly et al. (2013) operationalized smoking susceptibility as answering anything but “definitely not” to two questions from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH): “If one of your best friends offered you a cigarette would you smoke it?” and “At any time during the next 12 months do you think you will smoke a cigarette?” Susceptibility to smoking among never smoking youth decreased from 23% to 20% between 2002 and 2008.

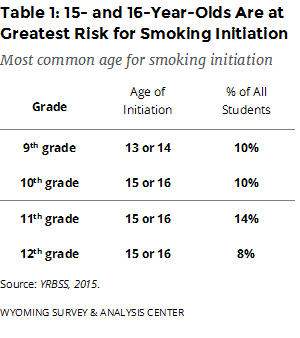

Smoking initiation is defined as the age at which a person first smokes one whole cigarette. According to the YRBSS (2015), teens aged 15 or 16 are at the highest risk for smoking initiation. More students in 10th, 11th, and 12th grades report smoking initiation at that age than at other ages (Table 1). As a point of reference, teens typically turn 15 during 9th grade, meaning relatively few 9th graders would be old enough to report starting smoking at that age.

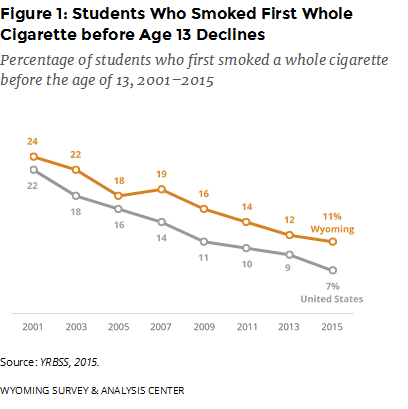

The percentage of Wyoming and U.S. high school students who smoked one whole cigarette before turning 13 declined between 2001 and 2015 (Figure 1; WY YRBS, 2015; YRBSS, 2015).

Age of Initiation: Adult Smokers

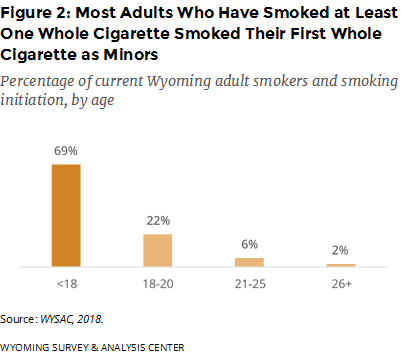

Overall, it is clear that most Wyoming adults who are or have been regular smokers began smoking before the legal age of 18. Among Wyoming adults who had smoked a whole cigarette, about seven out of 10 smoked their first whole cigarette when they were younger than 18 years old. Few (8%) started smoking after the age of 20 (Figure 2). Very few adults begin to smoke or begin to smoke daily after the age of 21; 15% of current and former daily smokers first began smoking daily when younger than 21 (WYSAC, 2018).

Youth Prevalence of Cigarette Smoking: Wyoming and the United States

Over time, preventing young people from starting to smoke and increasing the number of young smokers who quit can reduce the number of adults who smoke. Decreasing the prevalence of smoking among youth and adults can greatly improve community health (Institute of Medicine, 2015).

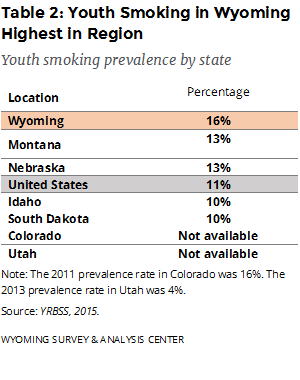

According to the 2015 YRBSS, Wyoming tied with Arkansas for the third highest smoking prevalence for youth. When compared to the four bordering states with available data, Wyoming had the highest youth smoking prevalence (Table 2; YRBSS, 2015).

Prevalence of Cigarette Smoking: Trends

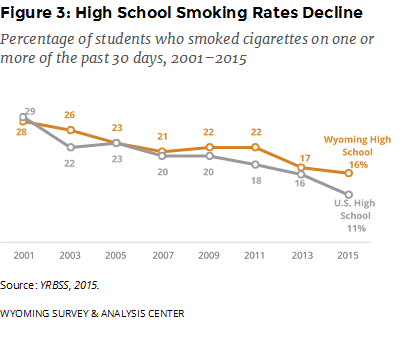

Between 2001 and 2015, the smoking rates for Wyoming and U.S. students declined. The trend among Wyoming high school students is similar to the national trend (Figure 3; YRBSS, 2015).

Quitting Smoking

The yearly percentage of Wyoming high school smokers who had attempted to quit in the 12 months prior to the survey declined from 58% in 2001 to 53% in 2015, Nationwide, the percentage declined from 57% in 2001 to 45% in 2015 (YRBSS, 2015).

Prevalence of Smokeless Tobacco Use

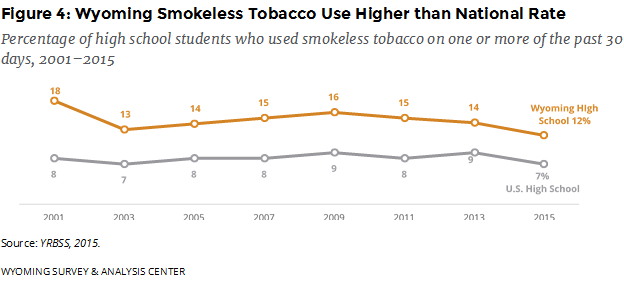

Based on use during the 30 days prior to being surveyed in 2015, smokeless tobacco use in Wyoming was more common among high school students (12%; YRBSS, 2015) than among adults (9% in 2015; Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System [BRFSS], 2016) and more common among high school young men (17%) than high school young women (6%; YRBSS, 2015).

Based on use during the 30 days prior to being surveyed in 2015, smokeless tobacco use in Wyoming was more common among high school students (12%; YRBSS, 2015) than among adults (9% in 2015; Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System [BRFSS], 2016) and more common among high school young men (17%) than high school young women (6%; YRBSS, 2015).

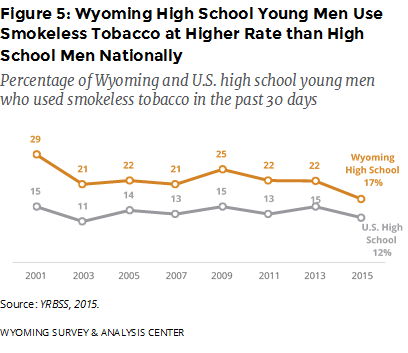

Prevalence of Smokeless Tobacco Use: Young Men

The rate for Wyoming high school young men using smokeless tobacco was lowest in 2015. Consistently since 2001, high school young men in Wyoming used smokeless tobacco at a significantly higher rate than high school young men nationally (Figure 5; YRBSS, 2015).

Prevalence of Youth Use of Electronic Delivery Systems (ENDS)

Electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS; also known as e-cigarettes, e-cigs, or vape-pens) are battery powered devices that produce an aerosol by heating a liquid instead of producing smoke from burning tobacco. Contents of the liquid vary across products, and some models allow for customized liquids. As of May 2016, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) considers ENDS to be tobacco products. Regulations prohibiting the sale of ENDS to minors went into effect on August 8, 2016.

Overall, 49% of Wyoming high school students had ever used ENDS, similar to the estimate of 45% nationwide. However, a greater percentage of Wyoming high school students (30%) are current ENDS users when compared to the national estimate (24%; YRBSS, 2015).

The YRBSS only asked about ENDS use in 2015, making a trend analysis impossible. Different data identify a rapid increase in ENDS use. Nationally, ENDS were the most commonly used tobacco product for high school students in 2016. The use of ENDS increased from 2% in 2011 to 12% in 2017 (Wang et al., 2018). In 2018, 21% of U.S. high school students were current ENDS users. This dramatic increase likely reflects the uptake of a new class of ENDS devices with high nicotine content, the potential for more discrete use in part because they resemble a USB flash drive, and a variety of flavors that may appeal to youth. The FDA has responded to this increase with proposed changes to regulations of ENDS (Cullen et al., 2018).

Community and Social Factors

Social and demographic factors play a role in youth tobacco initiation. Communities with low socioeconomic status, lower overall education, and higher unemployment tend to have a higher prevalence of youth smoking (Bernat, Lazovich, Forster, Oakes, & Chen, 2009). Tobacco use by peers (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012), perceived social acceptability of tobacco use among peers, and having a parent who smokes are strongly associated with youth initiation of tobacco use (Albers, Biener, Siegel, Cheng, & Rigotti, 2008).

Attitudes Regarding Cigarette Smoking

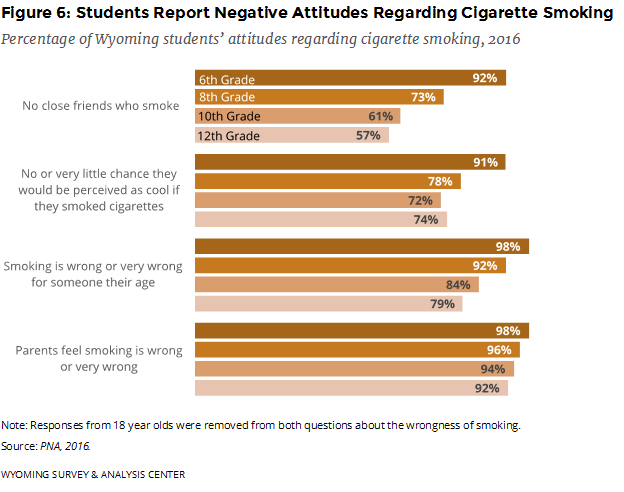

Results from the 2016 PNA indicate that Wyoming students generally hold negative attitudes about the use of tobacco. In general, students in higher grades had less negative attitudes toward tobacco use than students in lower grades.

When asked how many of their four best friends smoked cigarettes, most 6th, 8th, and 10th grade students reported they had no close friends who smoked. Similarly, a plurality of 12th grade students reported they had no close friends who smoked (Figure 6; PNA, 2016).

Most students in each grade reported there was no or very little chance they would be seen as cool if they smoked cigarettes, it was wrong or very wrong for someone their age (excluding 18-year-olds) to smoke cigarettes, or their parents felt it was wrong or very wrong for them (excluding 18-year-olds) to smoke cigarettes (Figure 6; PNA, 2016).

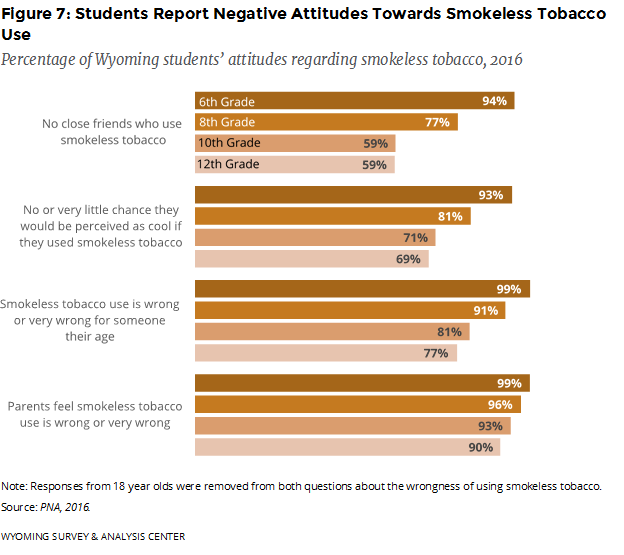

Attitudes Regarding Smokeless Tobacco Use

The pattern was similar for smokeless tobacco. The majority of Wyoming students in 6th, 8th, 10th, and 12th grades reported they had no close friends who used smokeless tobacco, there was no or very little chance they would be seen as cool if they used smokeless tobacco, it was wrong or very wrong for someone their age (excluding 18-year-olds) to use smokeless tobacco, or their parents felt it was wrong or very wrong for them (excluding 18-year-olds) to use smokeless tobacco (Figure 7; PNA, 2016).

References

Albers, A. B., Biener, L., Siegel, M., Cheng, D. M., & Rigotti, N. (2008). Household smoking bans and adolescent antismoking attitudes and smoking initiation: Findings from a longitudinal study of a Massachusetts youth cohort. American Journal of Public Health, 98(10), 1886-1893. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.129320

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System [Datafile 1995-2016]. (2016). Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved April 25, 2016, from http://www.cdc.gov/brfss.

Bernat, D. H., Lazovich, D., Forster, J. L., Oakes, J. M., & Chen, V. (2009). Area-level variation in adolescent smoking. Preventing Chronic Disease, 6(2), 1-8. Retrieved June 18, 2012, from http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2009/apr/08_0048.htm.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Preventing Initiation of Tobacco Use: Outcome Indicators for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs–2014. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). Promoting quitting among adults and young people: outcome indicators for comprehensive tobacco control programs—2015. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health.

Cullen, K. A., Ambrose, B. K., Gentzke, A. S., Apelberg, B. J., Jamal, A., King, B. A. (2018). Notes from the Field: Use of Electronic Cigarettes and Any Tobacco Product Among Middle and High School Students — United States, 2011–2018. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67, 1276–1277. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6745a5

Farrelly, M. C., Loomis, B. R., Han, B., Gfroerer, J., Kuiper, N., Couzens, G. L., … Caraballo, S. (2013). A comprehensive examination of the influence of state tobacco control programs and policies on youth smoking. American Journal of Public Health, 103(3), 549-55. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300948

Institute of Medicine. (2015). Public health implications of raising the minimum age of legal access to tobacco products. Committee on the Public Health Implications of Raising the Minimum Age for Purchasing Tobacco Products, Board on Public Health and Public Health Practice, Institute of Medicine, The National Academies. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/18997

Prevention Needs Assessment [Data File 2001–2016]. (2016). Laramie, WY: Wyoming Survey & Analysis Center, University of Wyoming. Retrieved March 21, 2016, from http://www.pnasurvey.org/

Singh, T., Arrazola, R. A., Corey C. G., Husten, C. G., Neff, L. J., Homa, D. M., King, B. A. (2016). Tobacco use among middle and high school students – United States, 2011-2015. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 65, 361-367. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6514a1

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2014). Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. (Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-48, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4863). Rockville, MD. Retrieved March 24, 2016, from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files /NSDUHresultsPDFWHTML2013/Web/NSDUHresults2013.pdf.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2012). Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. Retrieved January 8, 2013, from http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports /preventing-youth-tobacco-use/full-report.pdf

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2016). Extending Authorities to All Tobacco Products, Including E-Cigarettes, Cigars, and Hookah. Retrieved May 31, 2016, from http://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/Labeling/ucm388395.htm

Wang, T. W., Gentzke, A., Sharapova, S., Cullen, K. A., Ambrose, B. K., Jamal A. (2018). Tobacco Product Use Among Middle and High School Students — United States, 2011–2017. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67, 629–633. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6722a3

WYSAC. (2018). 2017 Wyoming Adult Tobacco Survey [Data file]. Laramie, WY: Wyoming Survey & Analysis Center, University of Wyoming.

Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System [Data File 1991–2015]. (2015). Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved June 13, 2016, from http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/yrbs/index.htm