Summary

The earlier young people begin using tobacco products, the more likely they are to use them as adults and the longer they remain users (Institute of Medicine, 2015). One of the four goals the Wyoming Tobacco Prevention and Control Program (TPCP) shares with the federal tobacco prevention and control program is to reduce youth initiation of tobacco use. Limiting youth access to tobacco products may help reduce youth initiation of tobacco use (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2014).

Tobacco retailers in Wyoming normally comply with Wyoming law regarding the sale of tobacco to minors (State of Wyoming, 2017; WYSAC, 2017a, 2017b). Continued educational and enforcement efforts will likely maintain this success.

Still, many students perceive that cigarettes are easily accessible (Prevention Needs Assessment [PNA], 2016), suggesting that minors in Wyoming may identify stores where they are likely to make successful purchase attempts or can rely on other ways of obtaining cigarettes, such as getting them from friends or relatives.

Two fifths of Wyoming’s high schools have comprehensive tobacco-free policies that prohibit all tobacco use at all times in all locations (Brener et al., 2017). Efforts to encourage schools to implement and enforce comprehensive tobacco-free policies—including for off-site events—could further reduce youth tobacco use in Wyoming.

Preventing Youth Access in Wyoming

One important piece of legislation regarding youth access is the 1992 Synar Amendment (Section 1926 of Title XIX, Federal Public Health Service Act). The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA, 2010) is responsible for enforcing this legislation and requires states to enact and enforce laws preventing the sale of tobacco to minors. In accordance with the Synar Amendment, Wyoming’s current youth access law (comprised of the eight sections of Wyoming Statute 14 Article 3; State of Wyoming, 2017) prohibits individuals from selling or delivering tobacco products to minors (youth under the age of 18) and prohibits minors from purchasing, possessing, or using tobacco, including electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS; also known as e-cigarettes). In 2000, Wyoming implemented a three-pronged approach to reduce youth access to tobacco products (Wyoming Department of Health, Public Health Division, 2014). This approach currently consists of the following actions:

Education through the Got ID? Program. The Wyoming Association of Sheriffs and Chiefs of Police (WASCOP), working with local community members, provides packets to tobacco retailers that educate the retailers about restricting sales of tobacco products to minors.

Synar inspections to monitor compliance without penalties for violations. During Synar inspections, trained 16- and 17-year-old inspectors use standardized protocols to attempt to purchase cigarettes or smokeless tobacco from a sample of Wyoming tobacco retailers accessible to minors.

Law enforcement inspections. WASCOP conducts compliance inspections in addition to the Synar inspections. During WASCOP inspections, trained adolescent inspectors attempt to purchase cigarettes from Wyoming tobacco retailers. Unlike Synar inspections, these compliance checks allow law enforcement officers to issue citations to merchants who sell to minors.

The U. S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) also enforces laws against selling tobacco to people younger than 18.

Because retail access is only one of the ways youth can access cigarettes, this issue brief also includes student reports about how they access tobacco products and how easy they think it would be to get cigarettes. School restrictions are another regulatory approach to reduce youth access to tobacco products.

Synar Inspection Results

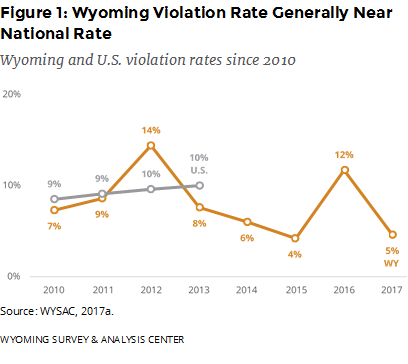

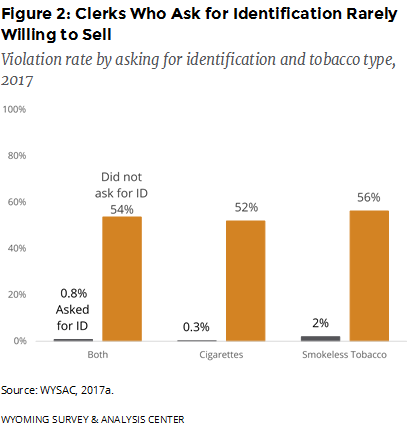

SAMHSA (2010) requires states to have a Synar violation rate under 20%. Despite changes to inspection methods over time (e.g., adding smokeless tobacco inspections in 2010), Wyoming’s Synar violation rate has generally been between 4% and 10% since 2000. The two exceptions were in 2012 and 2016 when three inspection trips (one in 2012, two in 2016) with high violation rates raised the state rates. In 2017, Wyoming’s violation rate was 4.6% (Figure 1). Clerks asking inspectors for identification has consistently been the strongest predictor of violations; clerks who ask for an ID (which inspectors do not provide) are unlikely to sell tobacco to a minor (see Figure 2 for the 2017 data; WYSAC, 2017a).

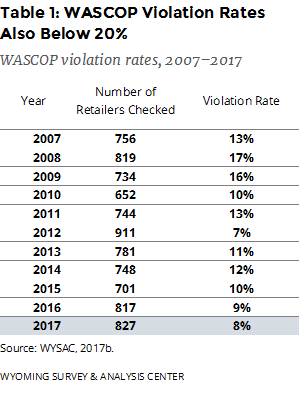

WASCOP Inspection Results

Table 1 shows the results of WASCOP inspections (WYSAC, 2017b). Violation rates measured by the WASCOP inspections have been lower than 20% since 2007.

FDA Inspection Results

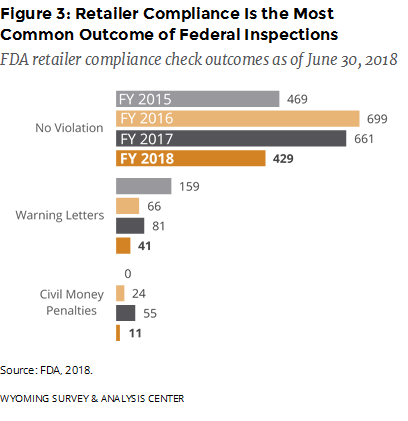

The Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act authorized the FDA to conduct law enforcement inspections for underage sales of tobacco products, including revisiting retailers found to be in violation (FDA, 2015). In Wyoming, the FDA has conducted inspections during four fiscal years. The FDA conducted 628 inspections in fiscal year 2015 (July 2014 to June 2015) in Wyoming, 789 inspections in fiscal year 2016, 797 in fiscal year 2017, and 481 in fiscal year 2018. The FDA’s first enforcement action is a warning letter notifying a retailer of the violation and explaining the other penalties. The second level of enforcement action is a civil money penalty for repeated violations. Finally, the FDA may issue a no-tobacco-sale order prohibiting the retailer from selling tobacco for a specific period of time if there have been at least five violations in three years (FDA, 2016). Most inspections in Wyoming found no violations, but the FDA has issued warnings and civil money penalties, but zero no-tobacco-sale orders (Figure 3; FDA, 2018).

Cigarette Purchases by Youth

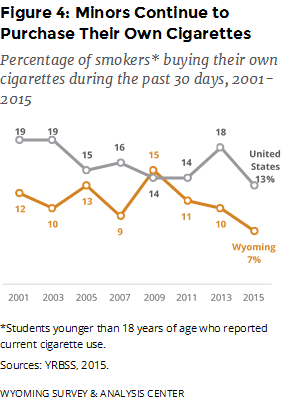

In 2015, 7% of Wyoming high school smokers younger than 18 years of age reported that they usually got their own cigarettes by buying them in a store or gas station. This percentage has been somewhat erratic since 2001 in both Wyoming and the United States (Figure 4; Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System [YRBSS], 2015).

Youth Perceived Access to Cigarettes

Limiting retail availability of cigarettes for youth is only part of restricting youth access to cigarettes. The development and implementation of programs to limit youth access to tobacco through means other than direct purchases could further reduce youth initiation of tobacco use and consumption of tobacco. Non-retail sources include relatives, unrelated adults or minors, buying it themselves, taking it, and other non-specified sources (PNA, 2016 [based on 2014 data as the most recent year the question was asked]; YRBSS, 2015).

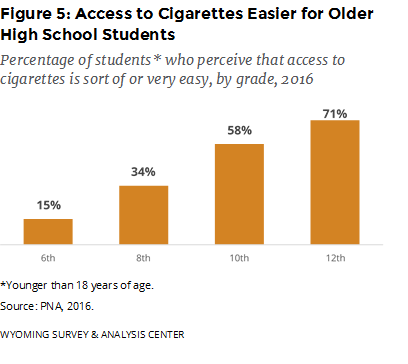

In 2016, 24% of Wyoming middle school students and 61% of Wyoming high school students under the age of 18 said it would be easy (either sort of easy or very easy) to “get some cigarettes.” The perceived ease of access to cigarettes varied by students’ grade level. In general, students in higher grades perceived access to cigarettes as easier than students in lower grades (Figure 5; PNA, 2016).

Tobacco Restrictions at School

Implementing comprehensive tobacco-free polices on school property will likely reduce susceptibility to experimentation with tobacco products, youth initiation of tobacco products, and overall youth use of tobacco (CDC, 2014). School policies also make it more difficult for youth to use tobacco products during much of the day. A school is considered tobacco free when there is a policy that specifically prohibits the use of all types of tobacco (including cigarettes, smokeless tobacco, cigars, and pipes, but not necessarily ENDS) by all people (students, faculty, staff, and visitors), at all times (including during non-school hours), and in all places (including school-sponsored events held off campus). In 2016, 40% of Wyoming’s high schools were smokefree, often missing out on that designation because of policies related to off-site events (Brener et al., 2017).

References

Brener, N. D., Demissie, Z., McManus, T., Shanklin, S. L., Queen, B., & Kann, L. (2017). School health profiles 2016: Characteristics of health programs among secondary schools. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Preventing initiation of tobacco use: outcome indicators for comprehensive tobacco control programs–2014. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. Retrieved January 3, 2018, from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/profiles/pdf/2016/2016_Profiles_Report.pdf

Institute of Medicine. (2015). Public health implications of raising the minimum age of legal access to tobacco products. Committee on the Public Health Implications of Raising the Minimum Age for Purchasing Tobacco Products, Board on Public Health and Public Health Practice, Institute of Medicine, The National Academies. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/18997

Prevention Needs Assessment [Data File 2001–2016]. (2016). Laramie, WY: Wyoming Survey & Analysis Center, University of Wyoming.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2015). Overview of the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. Retrieved March 28, 2016, from http://www.fda.gov/downloads /tobaccoproducts/labeling/rulesregulationsguidance/ucm336940.pdf

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2016). Civil money penalties and no-tobacco-sale orders for tobacco retailers (revised): Guidance for industry. Retrieved April 18, 2019, from https://www.fda.gov/downloads/TobaccoProducts/Labeling/RulesRegulationsGuidance/UCM252955.pdf

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2018). Compliance Check Inspections of Tobacco Product Retailers (through 06/30/2018). Retrieved July 13, 2018, from https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/oce/inspections/oce_insp_searching.cfm

Wyoming Department of Health, Public Health Division. (2014). Report to Governor Matthew H. Mead and the Joint Labor, Health, and Social Services Interim Committee: Report on tobacco settlement funds: Tobacco prevention and control program W.S. §9-4-1203 and §9-4-1204, by J. D’Eufemia & W. Braund. Retrieved April 25, 2016, from http://legisweb.state.wy.us/InterimCommittee/2014/WDH-TobaccoSettlement.pdf

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Substance Abuse Prevention. (2010). Implementing the Synar regulation: Tobacco outlet inspection. Retrieved October 1, 2010, from CSAP’s State Online Resource Center (SORCE) http://sorce.eprevention.org

State of Wyoming. (2017). Statute 14-3-3, Sale of Tobacco. Cheyenne, WY: Wyoming State Library, Legislative Service Office, Wyoming State Archives, Wyoming State Legislature. Retrieved March 8, 2017, from http://legisweb.state.wy.us/NXT/gateway.dll?f=templates&fn=default.htm

WYSAC. (2017a). Synar 2017 (FFY 2018) report: Synar Inspection Study and Electronic Nicotine Delivery System (ENDS) Pilot Study, by L. H. Despain & J. Penner. (WYSAC Technical Report No. CHES-1736). Laramie, WY: Wyoming Survey & Analysis Center, University of Wyoming.

WYSAC. (2017b). Wyoming alcohol and tobacco sales compliance checks, 2017, by W. T. Holder, (WYSAC Technical Report No. SRC-1708). Laramie, WY: Wyoming Survey & Analysis Center, University of Wyoming.

Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System [Data File 1991–2015]. (2015). Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved June 13, 2016, from