Summary

Each year between 2005 and 2009, about 41,000 nonsmoking people in the United States died prematurely from heart disease or lung cancer caused by exposure to secondhand smoke (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2014). One of the four key goals the Wyoming Tobacco Prevention and Control Program (TPCP) shares with the federal tobacco prevention and control program is to decrease exposure to secondhand smoke (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2017a). The majority of Wyoming adults agree with the statement, “Secondhand smoke is very harmful to one’s health.” Further, 79% of Wyoming adults would support a law making the indoor areas of restaurants smokefree, and 80% would support a law for smokefree indoor work areas (WYSAC, 2018). Enactment, implementation, and enforcement of smokefree policies and laws protect the public from the dangers of secondhand smoke. Yet, 71% of Wyoming residents are not covered by a comprehensive smokefree indoor air law, making them vulnerable to secondhand smoke in public places.

If the number of smokefree policies and laws in Wyoming increases, more residents will live, dine, and work in smokefree environments. In time, the associated decrease in their exposure to carcinogens and other toxins should lead to a decrease in sickness and death caused by tobacco smoke (CDC, 2017a).

Smokefree Rules in the Home

Nonsmokers who live with people who smoke are more likely to be exposed to secondhand smoke than nonsmokers who do not live with smokers. Children and youth between the ages of 3 and 19 are especially likely to report exposure to secondhand smoke when they live with a smoker, suggesting that exposure at home is common (Kaufmann et al., 2010). In 2015, 32% of Wyoming adult smokers who lived with children younger than 17 said they never smoke in front of their children (WYSAC, 2017a).

The risks to children exposed to secondhand smoke include SIDS, middle ear disease, respiratory symptoms, impaired lung function, lower respiratory illness, and asthma (USDHHS 2010). Children depend on the adults in their homes to set and follow rules that could protect them from exposure to secondhand smoke. In cases where secondhand smoke may enter a home from another residence (such as in multi-unit housing), children and adults depend on the rules in their community. Because secondhand smoke lingers in the air of a home even when a person is not actively smoking, parents who smoke while their children are away from home are still exposing that child to secondhand smoke. Similarly, designating a smoking room still exposes others to secondhand smoke (USDHHS, 2006).

About one in ten adults in Wyoming allow smoking in their homes. Between 2002 and 2017, the percentage of respondents who allow smoking inside their home decreased by almost half, from 28% to 11% (WYSAC, 2018). In 2010, the U.S. average was 18% (CDC, 2013).

Tobacco-Free Policies: Wyoming High Schools

Children also depend on policies set by adults to protect them from secondhand smoke at school and at off-campus, school-sponsored events. A school policy is considered tobacco-free when there is a policy that specifically prohibits the use of all types of tobacco (including cigarettes, smokeless tobacco, cigars, and pipes, but not necessarily electronic nicotine delivery systems [ENDS]) by all people (students, faculty, staff, and visitors) at all times (including during non-school hours) and in all places (including school-sponsored events held off campus). According to the Wyoming 2016 School Health Profiles Report: Trend Analysis Report (2017), 40% of Wyoming high schools had tobacco-free policies, a statistically significant decrease from 50% in 2014. Off-campus events at locations that allow visitors to smoke or use other tobacco products are a key factor in keeping Wyoming schools’ policies from being tobacco free as are policies that do not include cigars or pipes.

Children also depend on policies set by adults to protect them from secondhand smoke at school and at off-campus, school-sponsored events. A school policy is considered tobacco-free when there is a policy that specifically prohibits the use of all types of tobacco (including cigarettes, smokeless tobacco, cigars, and pipes, but not necessarily electronic nicotine delivery systems [ENDS]) by all people (students, faculty, staff, and visitors) at all times (including during non-school hours) and in all places (including school-sponsored events held off campus). According to the Wyoming 2016 School Health Profiles Report: Trend Analysis Report (2017), 40% of Wyoming high schools had tobacco-free policies, a statistically significant decrease from 50% in 2014. Off-campus events at locations that allow visitors to smoke or use other tobacco products are a key factor in keeping Wyoming schools’ policies from being tobacco free as are policies that do not include cigars or pipes.

Exposure to Secondhand Smoke in the Workplace

The proportion of Wyoming adults working indoors who are protected by smokefree polices at indoor workplaces increased slightly from 89% in 2010 to 93% in 2017. However, without consideration of workplace policies, 20% of Wyoming adults who work indoors reported exposure to secondhand smoke while at work during the previous week (WYSAC, 2018).

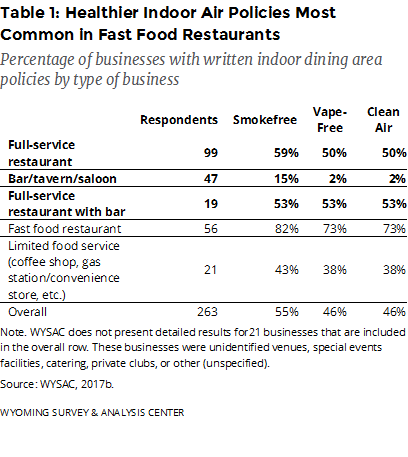

Voluntary smokefree policies in restaurants, bars, and other businesses also provide some protection from secondhand smoke (Guide to Community Preventive Services, 2015). In 2016, about half (51%) of Wyoming dining businesses (including bars) had a written policy about smoking or vaping. Written policies prohibiting smoking and vaping for all indoor areas (labeled Clean Air in Table 1) were most common among fast food restaurants. Full-service restaurants were more likely to have clean air policies than full-service restaurants with attached bars. Bars, taverns, and saloons (as a single category) were the least likely business type to have clean air policies (Table 1; WYSAC, 2017b).

Voluntary smokefree policies in restaurants, bars, and other businesses also provide some protection from secondhand smoke (Guide to Community Preventive Services, 2015). In 2016, about half (51%) of Wyoming dining businesses (including bars) had a written policy about smoking or vaping. Written policies prohibiting smoking and vaping for all indoor areas (labeled Clean Air in Table 1) were most common among fast food restaurants. Full-service restaurants were more likely to have clean air policies than full-service restaurants with attached bars. Bars, taverns, and saloons (as a single category) were the least likely business type to have clean air policies (Table 1; WYSAC, 2017b).

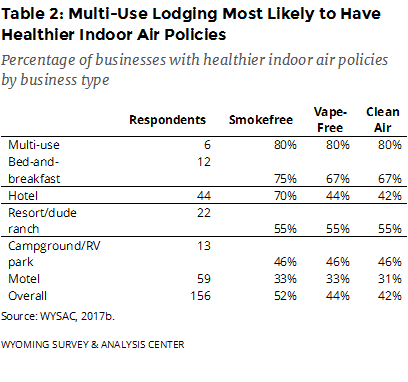

In 2016, the prevalence of clean air policies differed across lodging business type. Indoor clean air policies were most common in multi-use businesses (e.g., a business that is both a motel and campground). Motels were the least likely to have smokefree and vape-free policies (WYSAC, 2017b; Table 2).

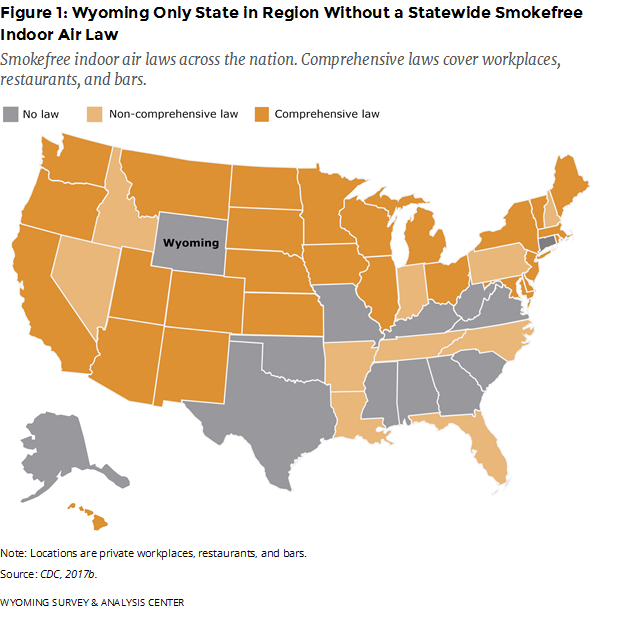

Smokefree Indoor Air Laws: Wyoming and Across the Nation

Enacting comprehensive smokefree indoor air laws is one of the best ways to protect nonsmokers from secondhand smoke (USDHHS, 2006). As of January 2018, Wyoming did not have a statewide smokefree indoor air law. However, every one of the six states bordering Wyoming had some sort of statewide smokefree indoor air law. Five of the six bordering states have a comprehensive smokefree indoor air law that covers private workplaces, restaurants, and bars (Figure 1; CDC, 2017b).

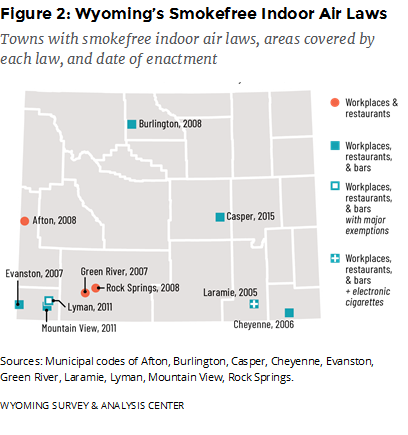

Smokefree Indoor Air Laws in Wyoming

Since the city of Laramie enacted Wyoming’s first smokefree indoor air law in 2005, the number and coverage of Wyoming’s smokefree indoor air laws have increased (Figure 2). The current laws throughout Wyoming differ with regard to covering bars. Six cities in Wyoming have comprehensive smokefree indoor air laws. Three additional laws cover workplaces and restaurants, but not bars. A law in Lyman allows business owners to opt out by prominently displaying signs identifying the business as a smoking establishment (Lyman Municipal Code, 2011). Without data about the decisions of all individual business owners in Lyman, WYSAC does not include Lyman residents as covered by a smokefree indoor air law. Casper enacted a comprehensive smokefree indoor air law in 2012, exempted bars in 2013, and amended the law in 2015 to make it comprehensive again (Casper Municipal Code, 2015; Richards, 2015) This amendment, along with the other smokefree indoor air laws, means that 29% of the state’s population is covered by a comprehensive smokefree indoor air law (Census estimates [ca.2017]; Municipal codes of Afton, 2008; Burlington, 2008; Casper, 2015; Cheyenne, 2006; Evanston, 2007; Green River, 2007; Laramie, 2005; Lyman, 2011; Mountain View, 2011; Rock Springs, 2008).

Adults Have Negative Attitudes toward Secondhand Smoke

In 2015, most Wyoming adults had negative attitudes toward secondhand smoke. Almost all, 97%, of adults reported that breathing smoke from other people’s tobacco products was very (62%) or somewhat (35%) harmful to one’s health (WYSAC, 2018).

Support for Smokefree Indoor Areas of Workplaces, Restaurants, and Bars

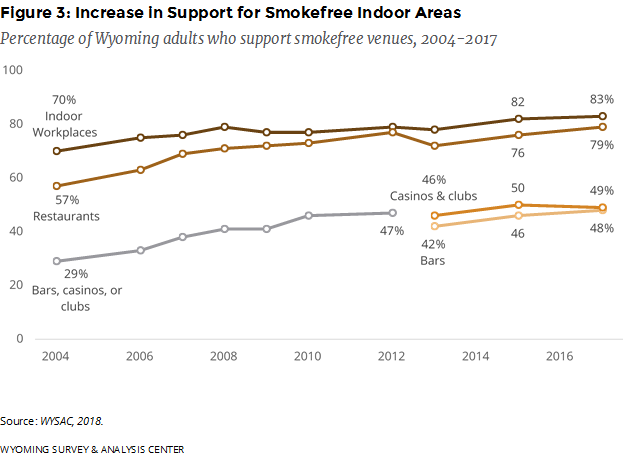

Support for smokefree indoor areas of restaurants and bars, casinos, or clubs has significantly increased through 2017 (Figure 3). The majority of Wyoming adults (83%) reported in 2017 that smoking should never be allowed in indoor workplaces, an increase from 71% in 2002. Support for eliminating secondhand smoke from indoor dining areas of restaurants grew from 57% of Wyoming adults in 2002 to 79% in 2017. Similarly, support for eliminating secondhand smoke from indoor areas in bars, casinos, or clubs grew from 29% of Wyoming adults in 2004 (the question was not included in 2002 and changed after 2012) to 47% in 2012 (WYSAC, 2018).

Support for smokefree indoor areas of restaurants and bars, casinos, or clubs has significantly increased through 2017 (Figure 3). The majority of Wyoming adults (83%) reported in 2017 that smoking should never be allowed in indoor workplaces, an increase from 71% in 2002. Support for eliminating secondhand smoke from indoor dining areas of restaurants grew from 57% of Wyoming adults in 2002 to 79% in 2017. Similarly, support for eliminating secondhand smoke from indoor areas in bars, casinos, or clubs grew from 29% of Wyoming adults in 2004 (the question was not included in 2002 and changed after 2012) to 47% in 2012 (WYSAC, 2018).

References

Afton, Wyoming, Municipal Code §6-8-04 (2008).

Burlington, Wyoming, Municipal Code §8-64-40 (2008).

Casper, Wyoming, Municipal Code §8-16 (2015).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Tobacco Control State Highlights 2012. Atlanta, Georgia: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office on Smoking and Health. Retrieved January 28, 2013, from http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/state_data/state_highlights/2012/sections/index.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017a). Eliminating exposure to secondhand smoke: Outcome indicators for comprehensive tobacco control programs–2017. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017b). State tobacco activities tracking and evaluation (STATE) system. Retrieved October 23, 2017, from https://www.cdc.gov/ statesystem/index.html

Cheyenne, Wyoming, Municipal Code §8-64-040 (2006).

Evanston, Wyoming, Municipal Code §10-4 (2007).

Green River, Wyoming, Municipal Code §18-93 (2007).

Kaufmann, R. B., Babb, S., O’Halloran, A., Asman, K., Bishop, E., Tynan, M., … Blount, B. (2010). Vital signs: Nonsmokers’ exposure to secondhand smoke—United States, 1999–2008. MMWR, 59(35), 1141-1146.

Laramie, Wyoming, Municipal Code §8-56-030 (2005).

Lyman, Wyoming, Municipal Code §4-4-5 (2011).

Mountain View, Wyoming, Municipal Code § 4-6-5 (2011).

Richards, H. & Meyer, B. (2015, November 3). Voters approve full smoking ban in Casper. Retrieved March 29, 2016, from http://trib.com/news/local/casper/voters-approve-full-smoking-ban-in-casper/article_30b31207-c7c1-5de4-b203-fa01e4a6b594.html

Rock Springs, Wyoming, Municipal Code §4-1604 (2008).

U.S. Census Bureau. [ca. 2017]. American fact finder [user interface tool]. Retrieved December 4, 2017, from http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2006). The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coordinating Center for Health Promotion, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2010). How tobacco smoke causes disease: The biology and behavioral basis for smoking-attributable disease: A report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of Surgeon General.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2014). The health consequences of smoking: 50 years of progress. A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health.

Wyoming 2016 School Health Profiles report: Trend analysis report. (2017). Retrieved December 18, 2017, from https://1ddlxtt2jowkvs672myo6z14-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/2016WY-Trend-Report.pdf

WYSAC. (2018). 2017 Wyoming Adult Tobacco Survey [Data file]. Laramie, WY: Wyoming Survey & Analysis Center, University of Wyoming.

WYSAC. (2017). 2016 Hospitality Survey: Smoke- and vape-free policies in Wyoming’s dining, drinking, and lodging establishments, by L. Wimbish & L. H. Despain. (WYSAC Technical Report No. CHES-1660). Laramie, WY: Wyoming Survey & Analysis Center, University of Wyoming.